Harriet Washington, author of Medical Apartheid.

If white Americans know anything about the dark history of American medicine and Black people, they’ve likely at least heard of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. But as author Harriet Washington explains, Tuskegee was just one example in “a sea of abusive and, frankly, racist experimentation.”

Transcript

Osha Davidson 00:00

If White Americans know anything about the dark side of the history of American medicine and Black people, they’ve likely at least heard of the Tuskegee syphilis study.

Ernest Hendon 00:10

It was a program they said was helping the people, you know, on it. If they join that they could get some medical care. I might’ve been 20 years old. I never could understand what it was all about.

Osha Davidson 00:31

That was Ernest Hendon, one of the victims of the experiment that began in 1932. Hundreds of Black men in Macon County, Alabama, who tested positive for syphilis weren’t told they were infected, and they were never treated for the disease. The study ended in 1972, and then only because it was exposed in an Associated Press story. Of course, it’s good that most Americans have at least heard of this terrible chapter in our history. But there is a problem with the surface knowledge of the Tuskegee experiment.

Harriet Washington 01:15

The thing about Tuskegee is that people are more likely to be aware of it. But unfortunately in people who are more likely to be aware of it are less likely to be aware that it was only one experiment in a sea of abuses and, frankly, racist experimentations.

Osha Davidson 01:29

That’s Harriet Washington, author of Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.

The book won the 2007 National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction. Washington, a former research fellow in medical ethics at Harvard Medical School, tells the largely unknown story of how the rise of medicine and slavery were inseparable in America and she documents how a legacy of medical racism still haunts Black Americans.

The infant mortality rate for Black babies is twice that for white babies. The maternal mortality rate for Black mothers is three to four times higher than for white mothers. These and other racial health disparities rarely make the news – because they’re not new. But that news blackout recently ended, at least temporarily, thanks to an unwelcome event.

Dr. Anthony Fauci 02:24

Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director, The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director, The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Unfortunately, when you look at the predisposing conditions that lead to a bad outcome with Coronavirus, the things that get people into ICUs that require intubation and often lead to death, they are just those very comorbidities that are, unfortunately, disproportionately prevalent in the African American population.

Osha Davidson 02:44

But once the COVID-19 crisis ends, will we go back to business as usual? A pessimist might point to what happened after then-President Bill Clinton’s impassioned call for change when he apologized to the victims of the Tuskegee experiment on May 16, 1997.

Bill Clinton

You were grievously wronged. I apologize. And I am sorry that this apology has been so long in coming. An apology is the first step. We can begin by making sure there is never again another episode like this one.

Osha Davidson 03:26

Symbolic gestures like apologies are a good first step, but they’re no substitute for real change. Clinton’s policy modifications were narrowly targeted, and he certainly didn’t take on institutionalized racism in medicine. An optimist could point to the fact that societies, like individuals, have the capacity to change for the better. It’s difficult but possible. And a realist? A realist might remind us that if we want change, we have to make change. Even pendulums don’t swing unless they’ve been pushed.

Osha Davidson 04:05

You write, “enslavement could not have existed without medical science.” What do you mean by that?

Harriet Washington 04:11

Enslavement in the Americas coincided with scientific developments like the development of animal husbandry, and with taxonomy, all of which were used, all these scientific efforts were used, to create a rationale for enslavement by portraying African Americans as subhumans who are essentially created in order to be servants. Not quite human, they didn’t occupy the human species. Interestingly, profoundly flawed in many ways in their bodies and minds, but strong in the ways that mattered.

A lot of scientific beliefs about African Americans supported enslavement. So the belief that they had very strong bodies and didn’t suffer from heat illness, for example, make them perfect for, you know, labor under the hot topical sun. And the belief that they didn’t succumb to certain illnesses that were common in that climate like malaria and yellow fever also added a net rationale for their enslavement.

But the belief that they were unintelligent and were not fully human sort of eased the conscience by saying it’s perfectly okay to work these people for long hours and to exploit their bodies in the medical setting because they’re not really human beings. The interesting thing about that is that at the same time, science provided a rationale for enslavement, enslavement also supported science. Because people insufficiently realize that medical science during that time was very different than it is today. It was a less prestigious profession. And many doctors had a very hard time making a living. You might finish your training, like a year or two in a southern college, but then you had to find patients and patients were hard to find…couldn’t charge much money.

And as Josiah Nott put it, a famous physician at the time, said the best practice is that among slaves. What he meant was that the doctors who were able to be successful and earn enough money to basically support themselves in dignity, were those who had contracts of slave owners to care for their slaves.

So science was necessary for enslavement. But doctors were also dependent on the slave system. There’s a really important symbiosis going on here. And if you had removed enslavement, you would have removed a lot of the support for medical science.

Osha Davidson 06:37

One thing I wanted to ask you about was you wrote about malingering and the idea of malingering and prescriptions, well, one thing that you wrote was the oil of hickory. But what was that prescription for?

Harriet Washington 06:53

Well, it’s actually a conflation of punishment and medical treatment. Very telling and often encountered in the literature of the period. Doctors often made these jocular references to applying nine drops of oil of hickory. Basically, you’re talking about whipping slaves, or nine drops of oil the raw high. So beating was considered a part of the appropriate treatment of slaves, both to subjugate and punish.

And in other contexts, you see that it’s used for like sexual motive…sexual gratification, but punishment and treatment were closely aligned when it came to enslaved people. For example, the slaves were affected with Drapetomania, that disease that caused slaves to run away. Well, Cartwright said the way to treat the slaves was to separate them from the other slaves, take them out into the woods, work them unmercifully and beat them, essentially. So, that was a very, you know, very frequent feature of Southern medical treatments.

It’s important to realize that, you know, one of the things I encountered very early on was a large number of people were saying, “Oh, but doesn’t make any sense that they would abuse slaves. I mean, they wanted their workforce to be healthy, right?” They wanted a healthy workforce in order to acquire their wealth. But people tend to confuse health and fitness for work. Because fitness for work was the goal when it came to enslaved people. When it came to whites, especially whites of property, then it was important to maintain their health. I mean that was relationship in western healing dyad, doctor-patient relationship, and a trusted relationship in which the doctor had a responsibility toward the patient and tried to care them and try to satisfy their desire to be healthy. But when it came to enslaved people, no one cared about the slave’s goals. It was all about the master’s goals.

Only the master could give permission for treatment and treatment was predicated on maintaining a fitness work, not health. There are lots of diseases that were perfectly compatible with the fitness for work. You had slaves who worked consistently malnourished, ridden with pesticides, mentally ill, a variety of illnesses. But they did not curtail their ability to work, and these illnesses tended to be ignored.

Osha Davidson 09:12

Well, most of your book deals with medical experimentation on Black Americans after slavery. And I guess the most famous example is the US Public Health Service’s Tuskegee study.

Harriet Washington 09:25

The thing about Tuskegee is that people are more likely to be aware of it, but unfortunately in people who are more likely to be aware of it, are less likely to be aware this was only one experiment in a sea of abusive, and frankly, racist experimentation. So people are more likely to hear of it, but they’re more likely to hear of it in isolation, and not to recognize it as part of a system of abuse, which is problematic.

So what actually happened in Macon County, Alabama. Despite the fact that it’s often referred to as the Tuskegee experiment, Tuskegee University had nothing to do with it. It frankly, was the United States Public Health Service’s experiment. And they conducted it in Macon County, the seat of which, Tuskegee University is located there. And in order to try to give it the patina of a multiracial enterprise, they titularly included Dr. Dibble, who was at Tuskegee, but it was only a nominal relationship. He actually had nothing to do with the study. They put his name on a few papers, that was it.

And essentially what they had done with Julius Rosenwald, the founder of Sears Roebuck and company, he was trying to improve the health of African Americans, but he lost his money in the stock market crash in 1929. One approach he had started or had wanted to start at Tuskegee, actually, he had to abandon for lack of funds, but the Public Health Service took it over and turned it into something totally different.

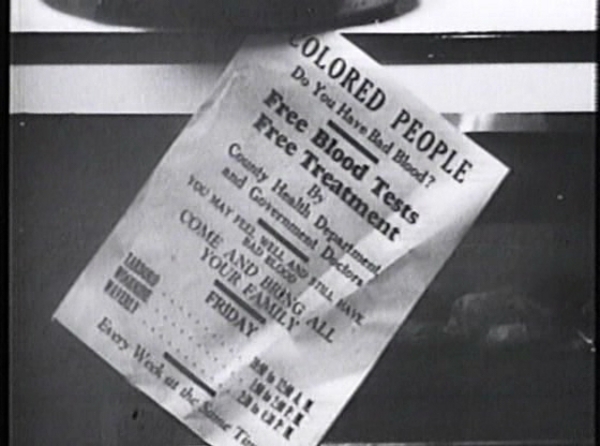

Rather than something that would improve the health of African Americans, they told the people, the Black people in the area, they were going to begin giving them health care. And in fact, they had a few open clinics that they announced they would get free medical examinations and treatment. And the clinics were completely thronged. I think by noon, they had 300 people there. The belief was, and they portrayed it as a munificent experiment. But in reality, what they wanted to do was they wanted to look at syphilis.

And they had a theory that syphilis affected the bodies and muscles of African Americans but did not affect their mind. That belief stemmed from 19th century scientists who said that African American neurological structures and systems were so primitive that African Americans didn’t suffer mental illness, they didn’t suffer neurological disease and the doctors and the Public Health Service wanted to prove that right. They decided to recruit Black men with syphilis and to study the ravages of syphilis in their bodies, periodically and consistently until these men died. There’s no treatment component. It was not a therapeutic experiment. They simply wanted to test them and then do a final autopsy in hopes of proving their theory that the brains of African Americans were not affected by syphilis, although the brains of whites were. And that’s exactly what they did.

They ended up recruiting 399 people who were tested positive for syphilis. And they had 200 controls, also African American men. And so they were heavily engaged tracking the men, doing tests every year, but they lied to the subjects telling the men that “Oh, we found you have bad blood, and we’re going to treat you.”

They gave them aspirin that were tinted pink, and they gave them painful spinal taps, and basically told the men they were getting treatment when they were not. They were simply having their blood titers checked. And so this went on for a very long time and the people engineering the study engaged in some herculean efforts to make sure that during the 40 years of the study — from 1932 to 72 — to make sure that these men would not get treatment for their syphilis. They didn’t want the men treated because the men who were treated successfully, that would ruin their, their experiment, you know, their study to trace their syphilis effects. So they did things like warn all the doctors in the area not to treat these men. They also gave a list of the men to the US Army and prevented them from enlisting in the army. They are afraid if they went into the army, it was, wartime had broken out by the 40s. They were afraid if they went into the army, they would get treatment for their syphilis in the army clinics. So they went to a lot of effort to do that.

So, this went on from 1932. And in 1972, there had been a few people over the years who had found out about the study, and they’d been outraged. Irwin Schatz in Detroit was a doctor who said, “I cannot believe, I’m reading this medical journal, I can’t believe you’re maintaining these men in a diseased state, a fatal illness. How can you do this?” And he wrote this outraged letter and in the archives, there’s a paper-clipped note on the letter that says, “We don’t intend to answer this.”

And we had Peter Buxtun, who was a low level interviewer in CDC, a Polish immigrant. He too was outraged. And he told me that he complained many times and their response was to sit him down and explain to him the finer points of medical ethics. He didn’t understand that the experiment was actually beneficent. When he left the CDC he became a lawyer and he tried repeatedly to get the study stopped. Finally he contacted a journalist friend who wrote a story about it for the AP. People found out about it, they were outraged, and the study finally stopped.

One of the interesting things about the study I see is that when people discuss the study, they almost never talk about the researchers’ stated motivation to try to prove the African Americans didn’t have neurological consequences from syphilis. They also don’t pay attention to how the study stopped. I write in Medical Apartheid a detailed long history of that and I was able to do that only because I called the people in the committee that ended the study. And around the time I called them, these people who were very old at that point and they were beginning to die off, but I spoke to most of them beforehand and was able to reconstruct it and it’s really an ugly story.

Osha Davidson 15:12

And you write that the Public Health Service regarded the man as “living cadavers.” What do you mean by that?

Harriet Washington 15:20

Their only interest, as Oliver Wenger said verbatim, “We have no further interest in these men until they die.” All they wanted was to be able to submit assessments over the years of how the disease had affected the men and then do an autopsy that would validate their opinion that syphilis didn’t affect the brains and nervous systems of Black people.

Osha Davidson 15:57

When I was reading your book, what came to my mind was the comparison to the infamous Nazi doctors. Is that an unfair comparison to make?

Harriet Washington 16:07

Perhaps unfair to the Nazis.

The thing is that the comparison to National Socialists doctors is one that can be made pretty consistently throughout American history, because the motivations are very similar.

Now, people, and rightly so, people are very wary about making comparisons between Nazi abuses and abuses elsewhere. And I understand that, that’s because so often the comparisons are actually not good comparisons. So often, the comparisons are to less dire research being conducted elsewhere, and therefore it can be, you know, insulting to survivors of the, you know, Nazi Holocaust. I understand that. But in this case, these are direct parallels. People focus on Tuskegee.

Tuskegee seems to be like the iconic study. But the reality is, most of the studies that I write about even both before and after enslavement, most are far worse than Tuskegee.

Like Tuskegee, James Marion Sims has captured people’s imagination. There’s a lot of interest in him. And for good reason. He really did epitomize, you know, some of the basic ethical conflicts in American researchers. But aside from that, he wasn’t terrifically important.

Osha Davidson 17:23

Is he the one who’s called the “Father of Gynecology…American Gynecology”?

Harriet Washington 17:27

Father of American gynecology, yeah. You know, you could say that about him. But then the question is, is that a good thing or a bad thing? You know, if you’re assuming that it’s a good thing, a munificent thing, then no. But think about it. One of the reasons why he is important, he epitomizes the American medical research that showed one face to most people, that is to white people, but another face to African Americans. He was a father of American gynecology in that he is lauded and lionized and praised and was influential and very, very powerful. In that sense, yes. But in the sense of truly caring for women? Of putting their health and rights and welfare first? No, even for white woman, I don’t think he was a champion that he’s portrayed as. And for Black women, he was definitely the exact opposite.

Osha Davidson 18:20

And what did he do to Black women?

Harriet Washington 18:23

There was a very devastating consequence of childbirth, vesicovaginal fistula, a horrible complication. The child would not be able to pass through the vaginal canal, would die, and then have to be taken out dead. But during the time the woman had spent in labor, fruitless labor, sometimes days, the pressure of the child’s head and body on her reproductive tract ended up causing holes after the child was taken away. So she would be left with openings between her rectum and vagina.

It was this very horrible situation. She was incontinent of urine and feces, recurrent infections, it was painful. Just a horrible, horrible problem and it would, you know, plague her for the rest of her life. But, in the south is struck far more Black women than whites. And Dr. Sims said, well it strikes Black women because Black women are dirty. And because they’re educated and they’re sexually profligate, and so, of course, they’re the ones with the highest rate. He decided that he was going to cure this disorder. He knew it would make his medical fortune. And so he decided he was gonna try to cure it.

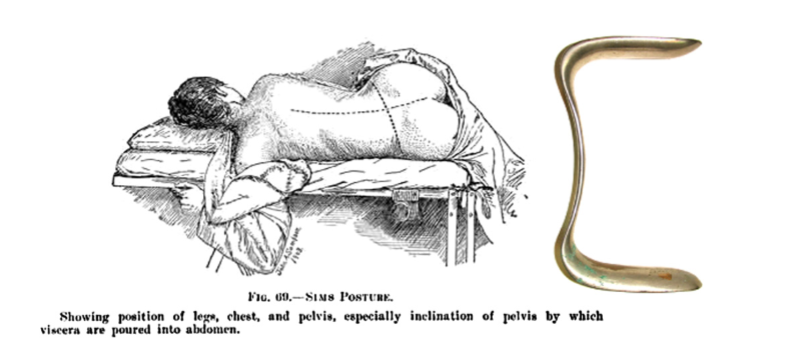

Sims position

Sims position

When he did, so he only used Black women. And that was not something that he only did. That’s something that doctors did in the south. They always use Black women to test their reproductive surgeries because you know, no woman wanted to undergo something like that, especially experimentally. No woman wanted to have her reproductive tract cut into to see whether something might work. The pain, the chances of infection during that time, both were very high and white women could say no. But Black women could not. If their masters gave their permission, if their masters lent the women, or rented the women to Sims, the woman had no choice. And that’s why Black women were used.

So over the course of five years, at least, he did many, many experimental surgeries, which were very difficult. They involved cutting repeatedly into women’s tissues, abrading them, roughing them up, sewing them together, and hoping that opening would stay closed. But it didn’t. It would always get infected, fall apart. And now the woman is even worse off than before. She still has the openings, she’s got the pain, recurrent infection, really horrible situation. One slave had about 30 surgeries over that five years. But finally, Sims hit upon using metal sutures, silver sutures, and they didn’t promote infection, and he was able to close one hole in one woman. So he became famous. He became rich just as he had hoped and was lionized as “the father of American gynecology.”

Osha Davidson 21:00

Did he use anesthesia?

Harriet Washington 21:02

Sims considered giving the women anesthesia and decided against it. I know because he wrote about himself. He wrote he considered giving them anesthesia, but it wasn’t worth the trouble and risk. Why would you say it wasn’t worth the trouble and risk? Because he had also written that the women were in horrible pain. He wrote about how one woman was screaming and in such agony, he thought she was going to die. But it still wasn’t worth the attendant trouble and risk. He wrote that, I think, because he was he was actually adopting this old theory that African Americans don’t feel pain the way whites do. And even though doctors knew this was not true, many of them knew it wasn’t true. Because they wrote of treating slaves in great pain. The belief was too valuable to discard, for it helped to support enslavement. It helped to support this idea of Black people as being inferior, and Sims subscribed to that. He said, I’ve thought about using it but it’s not worth the trouble because these were Black women after all.

Osha Davidson 22:03

I want to jump to something else. You have a chapter called the myth of the “crack baby.” And I wanted to ask you, what’s the mythic part?

Harriet Washington 22:10

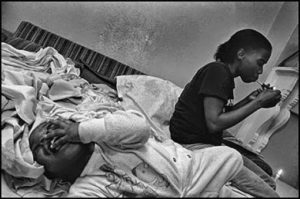

It was definitely a myth, no question about that. I was really gratified when I saw in a New York Times article actually refer to, they said that I had written 10 years ago, the crack baby was mythological. And now they were actually, they were agreeing. I was really happy about the fact that they have come around saying that because New York Times and many other prominent respected newspapers, and magazines and medical journals, had written in great depth about this crack baby, an entity that was like a miniature Golem. Because of the mother’s drug abuse, the baby was born, profoundly harmed, and doctors would describe it as being babies born without what makes them human. You know, they’re so profoundly damaged neurologically. And then, as the babies got a little bit older, there were headlines like: the crack babies are growing up, they’re going to be a fierce danger in schools. So these babies were characterized as some kind of miniature Golems.

The myth of the “crack baby.”

The myth of the “crack baby.”

And their mothers were demonized, quite vigorous, you know, these women would rather take crack, then, you know, give birth to a healthy baby. What happened was, none of that was true. It was a myth. Because the original article had written about not crack, but cocaine and effects and in only 20 children. What he found was [??] deficiency, but he said himself in his article, this is something that is worthy of further exploration, was to find out if children were being harmed by this, and if so, how much? But instead of doing those follow up studies, instead, we had a proliferation of media articles that changed the cocaine use to crack use and racialized it. And then you had a lot of doctors, unfortunately, weighing in with their anecdotal experiences in the hospital of babies who were profoundly damaged. And then finally, after years and years of publicity about crack babies who are completely racialized…I was a newspaper editor then and I had never seen a photo of a white crack baby. They were always by definition, Black. But Teratology did a very well refined study, and found that crack was not causing these problems. That the problems that had been cited by children in the medical studies were resulting from poverty. Because when they compared the kids to kids, other kids in poverty, profound poverty, whose mother had not been taking drugs or alcohol, they found the same deficits. So Teratology published analysis showing that this never existed. A media invention that, unfortunately, the medical profession, said vigorously. And so now it’s widely understood to be a myth. But when I wrote Medical Apartheid it was not. The same newspapers and articles that created this crack baby phenomena were not in a hurry to run an article showing, “Oh, by the way, we’re wrong, this never really happened.” And it really shows the power of the press and medical journalism to distort the image of African Americans.

Osha Davidson 25:19

Moving on to another horror is your writing about radiation studies.

Vertus Hardiman, victim of a radiation study.

Vertus Hardiman, victim of a radiation study.Harriet Washington 25:26

Very high doses of radiation have been used on African Americans, and sometimes for supposedly therapeutic purposes. But the therapeutic purposes, this doesn’t hold water. Sometimes even a cursory glance at the study makes you realize that this is not therapeutic at all. That this can’t possibly help the person. For example, University of Cincinnati, total body radiation was being used on cancer patients for tumors that were radioresistant. That meant that the tumors were already known not to respond to radioactivity. So why are you irradiating their entire bodies, a dose that experts knew would kill them, kill them after causing horrific pain and tissue destruction. And for no possible reason — was not going to be therapeutic. Interestingly, and his own colleague said, No, we’re not going to help them. Then he said, Well, I was experimenting. I was hoping to find that, you know, maybe some dose of this would actually be effective. And then he was asked, “Oh, you were experimenting? Did you get consent?” He produced consent forms, but they were questioned. One woman said, he produced a signed consent form from my grandmother, my grandmother never learned to read or write. So highly questionable. There is no possible justification for what he did. When his partner was asked, why did you choose Black subjects? I wrote in the book his verbatim quote, but it was along the lines of “Oh, these people were Black, they were poorly washed. They were available to us in the hospital.” He said this in 1995.

Osha Davidson 27:16

It seems like a common theme throughout all of this is that investigative studies became reframed as medical treatments. Is that accurate?

Harriet Washington 27:29

That is exactly what happened then. It’s exactly what’s happening today. I’m deeply concerned by the fact that today, this line between treatment and research is being effaced. And subjects are being recruited to research in a deceptive manner. They’re being told that, oh, we’re going to offer you this new cutting-edge treatment. Really, you’re using these people to further the end of other people. If anybody benefits from the study, it’s going to be people in the future. But people are being lied to. They’re being made to think that they’re patients, and they’re being treated. And the problem with being told that you’re a patient when you’re actually a subject is that patients have protections that subjects don’t have. Also, if you’re a patient, the focus is on you. The focus is on restoring your health, curing you, addressing your problems, tailoring things to the best possible outcome for you.

In research, that is not at all the paradigm. In research, the idea is looking to find something that’s going to help future patients and there’s no concern about whether it’s the best treatment for your not. Everyone’s going to get the same treatment in this arm of the study so that we can better collate and analyze our results. And if that turns out not to be a good treatment for you, well, too bad. That’s the luck of the draw. So it was a problem then and it’s a problem now,

Osha Davidson 28:52

The history of pervasive medical abuse seems to be linked with Black Americans’ distrust of doctors and the American medical establishment. If that’s so, how is that manifested today in the health of Blacks?

Harriet Washington 29:07

Actually, that’s the wrong question. Because we’re not just talking about African American wariness, or mistrust. We’re talking about an untrustworthy healthcare system. You can’t talk about African American wariness without talking about the nature of the system. Because, if you do, the implication is some pathology among African Americans. That’s not the case. African Americans who shun medical research and medical treatment? I feel it’s tragic that they’re shunning it. It’s a group that needs access to medical research and treatment more than other groups. But it’s a perfectly logical response. And the cure is not to change African American mentality or behavior. The cure is to create a healthcare system that is trustworthy. If it’s trustworthy, people will trust it.

Osha Davidson 30:02

We’ve been talking today with Harriet Washington, author of Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. If you have a question or comment about anything on our podcast or something we should have included but didn’t, we want to hear from you. Go to our website, www.TheAmericanProject.us.

Or you can always record your thoughts and send them by email to osha@TheAmericanProject.us. And please subscribe to our podcast on iTunes, Google Play, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.