Wilmington, North Carolina, was the closest America had come to a true post-racial society — until a bloody coup in 1898 destroyed the model for a democratic New South and laid the foundation for modern White Supremacy.

Transcript

When you hear the word coup d’état you’re thinking of another country. But something like that happened here, right in America. — Christopher Everett

Osha Davidson 00:19

The seaport of Wilmington, North Carolina was the closest America had come to a true post-racial society. This was before Barack Obama’s 2008 election made the term “post-racial” common. And so also before the term fell into disfavor as a wishful thinking post Ferguson, Missouri, and then openly mocked after the 2016 election of Donald Trump. But Wilmington, North Carolina was in fact, the real deal.

The largest and most prosperous city in the state had successful Black Law practices, real estate offices, doctors, and teachers. The police department was integrated as was the fire department. There were Black judges, the deputy clerk of court was Black. So was the county jailer, the county coroner, and several members of the city council. The local newspaper, The Wilmington “Daily Record” was the largest Black owned dateline in the United States, drawing advertisers from both Black- and White-owned businesses. This may not sound revolutionary until you consider that this wasn’t just pre-Obama. It was pre-JFK, and FDR, and his much older cousin, TR, Teddy Roosevelt. The Wilmington, North Carolina described here existed 122 years ago in 1898. Wilmington wasn’t just a success story for Black Americans. White residents who made up 40% of the population thrived to under a system known as Fusion politics. This multi-racial system created an egalitarian society with the working class of both races earning the highest average wages in the state. Historian and author David Cecelski:

David Cecelski 02:02

David Cecelski, author of “Democracy Betrayed.”

Events in North Carolina were showing the rest of the South and the rest of the country that there was a possibility for Blacks and Whites to cross racial lines and forge a different kind of politics. There are times where you can find enough common ground to start to bridge that gap and build a different kind of world.

Osha Davidson 02:20

Blacks and Whites coming together benefited both in a way never before seen in this country. Which is exactly why that successful model had to be destroyed.

I’m Osha Gray Davidson, producer and host of The American Project. Our first season is a deep dive into the issue of reparations for slavery and its legacy. In this episode, we look at how on November 10, 1898, White supremacists violently destroyed the model of racial cooperation that was Wilmington, North Carolina, turning the city into a different kind of example. The White terrorists showed the South and the entire nation that ethnic cleansing, including the mass murder of countless Black residents could be used to reassert White domination, without fear of any legal consequences.

Christopher Everett, Producer and director of “Wilmington on Fire.”

Christopher Everett 03:20

But this was an attack on American citizens, period.

Osha Davidson 03:23

That’s Christopher Everett, who produced and directed the award-winning 2015 documentary, “Wilmington on Fire.”

Christopher Everett 03:31

We’re not a perfect nation, and we have to learn from our mistakes. And this is one of the biggest mistakes we’ve ever made, was doing this massacre. It was a coup d’état. You know, when you hear the word coup d’état you’re thinking of another country, But something like that happened here, right in America.

Osha Davidson 03:48

For a dozen years following the Civil War, there was substantial, if imperfect racial progress in the South, as the federal government pursued a policy of democratization known as Reconstruction. That period ended when federal troops were withdrawn in 1877. But the battle for equal rights for all Americans continued. And nowhere was that fight more successful than in Wilmington, North Carolina. As White’s rolled back the progress of Reconstruction in state after state, Wilmington remained a beacon of hope. It’s almost a miracle that that light lasted nearly into the 20th century.

Again, Christopher Everett.

Christopher Everett 04:35

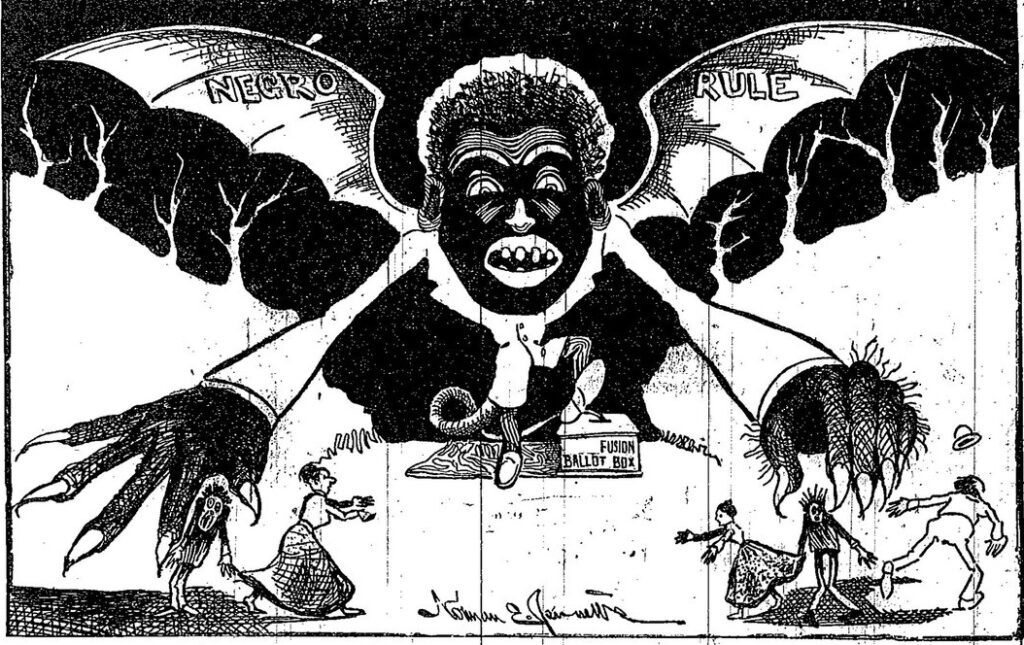

It was really what the New South was supposed to be, you know, after the Civil War, where you had all these folks working together and it was crazy because some of the political cartoons you would see they would have a picture of a Black person covering the whole state of North Carolina.

Then you have the stuff in South Carolina, they would just go crazy down there just suppressing African Americans. Virginia and all these other states. But North Carolina was key because of the whole Fusion movement of Whites and Blacks coming together, you know, because they just saw that, hey, we’re all we’re pretty much, yeah, we’re different in color, but we all want the same thing. You know, we want, you know, better schools for our kids, we want employment, we want to start businesses, and we want to engage in politics. So they say, you know what, let’s join forces and do that.

Osha Davidson 05:20

I asked Everett, to walk us through the events leading up to November 10th.

Christopher Everett 05:24

Well, you know, the tensions were high. People kind of, were hearing things that might happen, you know, guns were getting, you know, brought to the city. The racial tension was really, the elections of 1898 was happening. It wasn’t for the city or the county, it was just for the state. A lot of African Americans wanted to vote on the state level. But you had a lot of voter intimidation going on, you know, people changing up the ballot boxes, and just forcing people not to come to the polls, you know, threatening. The White supremacy candidates during that whole year, year and a half, we’re going all over North Carolina, pretty much spreading this whole White supremacy message.

Osha Davidson 06:00

There was nothing subtle about their campaign. They had no use for code words or dog whistles. One North Carolina party leader summed up the strategy this way.

Democratic Party leader 06:11

The slogan of the Democratic Party from the mountains to the sea will be but one word…

Osha Davidson 06:18

You can probably guess that slogan. It was the “N word.”

Christopher Everett 06:22

So they decided to take control of Wilmington because if you could take control of Wilmington, that was the main city at that time. That pretty much will set the precedent throughout the whole state.

Osha Davidson 06:33

The terrorists needed an excuse, a justification for their brutal actions on November 10. The one they settled on was far from original, but it had proved extremely effective at inciting White people to perpetrate violence against Black men.

Racist political cartoon, North Carolina.

Christopher Everett 06:49

Protecting White womanhood and you know these you know, Black beside here raping you know White women.

Osha Davidson 06:55

It started with this woman.

Rebecca Felton 06:58

Hello folks. Are you feeling good this morning? Hope you do. Thankful it’s as well as it is. I am pleased to see you.

Osha Davidson 07:08

That’s Rebecca Latimer Felton recorded at her Georgia home in 1929 when she was 94 years old. Felton’s main claim to fame is the fact that in 1922, she became the first woman to serve in the United States Senate. Well, first “ish.” An early leader of the suffrage movement for White women Felton and was rewarded with an appointment to fill a vacant Senate seat, a symbolic gesture that lasted just 24 hours. But for our purposes, Felton is more important for a speech she gave in August of 1897. She told her Georgia audience “if it needs lynching, to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts, then I say, lynch 1,000 times a week if necessary.”

Osha Davidson 08:01

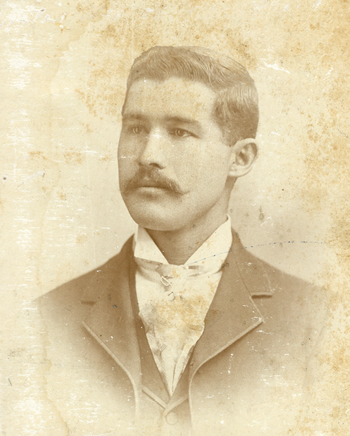

In case there’s any doubt about exactly who felt and wanted lynched, she elsewhere described young Black men who had never known the firm hand of slavery as “half-civilized gorillas” filled with “brutal lust” for White women. A year later, Wilmington’s White pro-Democratic newspapers the “Morning Star” ran Felton’s speech as part of the Democratic Party’s racist strategy. Alex Manly, the Black owner of the Wilmington “Daily Record,” responded with an editorial in his newspaper.

Alexander Manly, editor of the Wilmington “Daily Record.” Photograph from the John Henry William Bonitz Papers #3865, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Christopher Everett 08:32

He pretty much said that, you know, a lot of this stuff isn’t rape, you know, a lot of these women are willingly you know, having sexual affairs with Black men.

Osha Davidson 08:40

Rebecca Felton shot back, she told a reporter “when the Negro, Manly, attributed the cry of rape to lewd intimacy between Negro men and White women of the South, the slanderer has been made to fear a lyncher’s rope. White people went crazy. A Black man raping a White woman was the worst crime imaginable in the White psyche. But White women and Black men having consensual sex? That idea threatened to destroy the established social order. Here’s the late historian John Hope Franklin speaking in 2007, about the effect of Manly’s editorial

John Hope Franklin 09:21

That was putting not oil but gasoline on the fire. It blew up, blew up the town for Manly to suggest that.

Christopher Everett 09:58

You know, it really rallied up people…

Osha Davidson 10:01

Christopher Everett.

Christopher Everett 10:02

And also made people who were allies of the Fusion movement and African Americans, it kind of made them just take a fall back and say, you know what, maybe these people deserve this. If they have this attitude towards our women, even though we’re, you know, have an alliance, you know, if this is really true, maybe they are getting too uppity. And maybe these need to get back to the way it once was.

Osha Davidson 10:32

Just before the election, former Confederate officer Alfred Waddell told a crowd that conditions under Fusionist rule were intolerable. He proclaimed: “We are resolved to change them, if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.” On Election Day, November 8, 1898 ,the paramilitary force associated with the Democratic Party, the Red Shirts spread out throughout the city, threatening to kill Black residents if they attempted to vote. Democrats carried out a well-planned campaign of vote rigging stuffing ballot boxes in predominantly Black wards.

The Democrats swept the election. But not all offices had been up for election. And so some Fusionists remained in their positions. This was unacceptable to the White supremacists. Their plan all along was to not just defeat Wilmington multiracial movement. No, they were bent on eliminating it. On the morning after the election, they began the final phase of their operation. At a packed courthouse rally that morning, Democratic Party leaders unveiled a manifesto written to evoke the lofty rhetoric of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. They called their document the “White Declaration of Independence.”

White Declaration of Independence 11:58

Believing that the Constitution of the United States contemplated a government to be carried on by an enlightened people, believing that its framers did not anticipate the enfranchisement of an ignorant population of African origin. And believing that those men of the state of North Carolina who joined in forming the Union did not contemplate for their descendants, subjugation to an inferior race. We, the undersigned citizens of the city of Wilmington do hereby declare that we will no longer be ruled, and we will never again be ruled, by men of African origin.

Osha Davidson 12:50

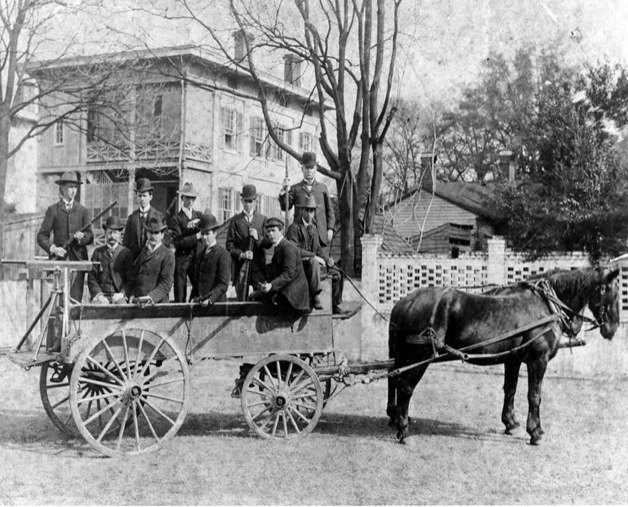

The proclamation ended by demanding that the Black newspaper The “Daily Record” be terminated, and its editor Alex Manly be exiled from the city forever. The carefully planned coup began at 8:15 on the morning of November 10, when Alfred Waddell gathered several hundred White men outside the armory of the Wilmington Light Infantry.

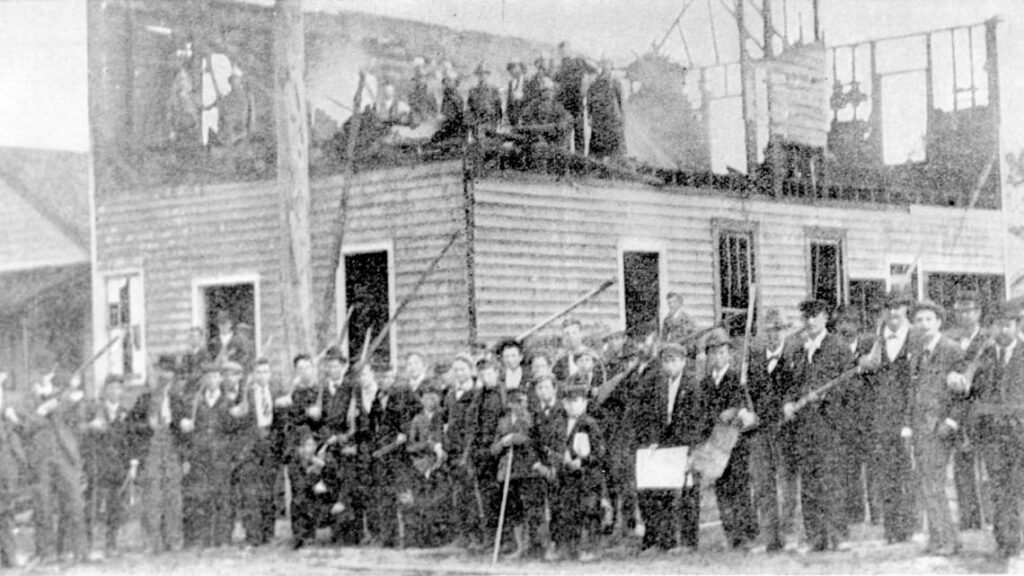

Wilmington Light Infantry with the cart-mounted ColtM1885 machine gun.

The infantry was the equivalent of today’s National Guard. Officially, they were under control of North Carolina republican governor Daniel Russell, a member of the Fusion movement. In reality, the Wilmington Light Infantry was now another wing of the Democrats. They took their orders from Waddell. The insurrectionists quickly emptied the building of firearms, including the recently invented machine gun. The Colt M1895, was an improvement over the already notoriously lethal hand-cranked Gatling gun. But the Colt was gas operated. The gun fired 400 belt-fed rounds in one minute with a lethal range of nearly two miles. It was literally a weapon of war.

Christopher Everett 14:02

They marched on Alex Manly’s newspaper building. Manly left, like I think maybe a day before that happened. I think they he got tipped off, and he left him and his brother left the town. Frank Manly was his brother, who he ran the paper with. They left. Luckily, they left because if they didn’t, they were going to get killed or lynched or worse. So they got there and burned down the building. And that’s the famous picture of anytime you look up the 1898 Wilmington massacre, that picture of all these White men with guns and stuff sitting around the burning building, that was when that happened.

The Wilmington “Daily Record” in ruins.

Osha Davidson 14:40

By this time, the crowd had swelled to several thousand armed White supremacists. Many had poured into Wilmington from other cities. Charles Aycock, who would become North Carolina’s governor two years later, was part of a group of 500 armed White men at the Goldsboro train station. They were waiting to board the Wilmington train when a telegram arrived, assuring them that the situation was well in hand, the building that housed Manly’s “Daily Record” was reduced to a smoldering ruin. Manly had already left town. But for the White supremacists, the day was just getting started.

Christopher Everett 15:18

After that, they went over to the Black community on the other side of town of Wilmington, and pretty much just started shooting folks.

There was sort of almost a genocidal execution of Black folks that was taking place in the city. — Duke University Professor William Darity.

Osha Davidson 15:34

In Everett’s documentary, Duke University Professor William Darity describes the mayhem.

Sandy Darity 15:41

You had armed bands of Whites who were roaming the city, and essentially indiscriminately killing Black people. So it was really effectively It was a slaughter. There’s a substantial controversy over how many people were actually killed. I believe that the state’s official report on the Wilmington riot, which I think is actually a fairly well-done report, says something to the effect that the maximum estimates are in the vicinity of about 60 folks who were killed. But if you read the report, and go through it page by page and count up the number of individuals who are reported to have been killed in the pages of the report, I think you get a figure that’s in excess of 100 people. I have no idea what the exact number is, you know. The stories have it that some bodies were literally thrown into the Cape Fear River. But there was sort of almost a genocidal execution of Black folks that was taking place in the city. And many people fled to the surrounding wooded areas and had to stay there until White tempers have had subsided.

Osha Davidson 16:59

But even for many of those who survived, there would be no return to Wilmington. State archivist LeRae Umfleet.

LeRae Umfleet 17:08

The banishment campaign had as its purpose to eliminate any potential for organization of the Black community to retaliate against what was happening, either politically, legally, or physically. And so some of the preachers and some of the other civic folks were rounded up, arrested, and put in jail overnight on the night of the tenth. And on the morning of the 11th they were told, get on this train, do not come back or else you will be killed.

Christopher Everett 17:44

So, a lot of those folks left they went to like places like Durham, North Carolina, Whitesboro, New Jersey, Philadelphia, Norfolk, New York just to start over.

Osha Davidson 17:54

Republican city officials who were part of the Fusion movement were forced at gunpoint to resign. They were replaced with Democratic Party loyalists. Alfred Waddell, leader of the coup and of the massacre of Black citizens, became mayor. Overnight, the population of the largest city in North Carolina went from majority Black to majority White. In more than a century that hasn’t changed. Wilmington today is 74% White, and just 20% Black. Of the 10 largest cities in North Carolina today, Wilmington is proportionally speaking, the Whitest place in the state.

Christopher Everett 18:33

After the massacre of 1819 happened, you know, that totally eliminated did the African American vote just through all this voter intimidation that came on because they elected a lot of folks on the state level. So therefore, they were able to put certain laws in place. And one of those laws was the grandfather clause, and it pretty much eliminated a lot of African American men to vote, period. And so they were able to get the governorship also in 1900. And so they put in more laws to cement that. That affected the whole state of North Carolina. The Black vote was pretty much gone after that, and this whole thing of Fusion politics, of Whites and Blacks coming together, was completely destroyed.

Osha Davidson 19:20

Wilmington’s beacon of hope for a New South had been extinguished. But even that wasn’t enough. The insurgents now in power worked to erase from public memory the fact that the beacon had ever existed and the brutal methods they used to demolish it.

David Cecelski 19:39

My name is David Cecelski and I’m a historian and freelance writer in Durham, North Carolina.

Osha Davidson 19:45

Cecelski edited one of the first books about the Wilmington massacre, “Democracy Betrayed.” I spoke with him by phone.

Osha Davidson 19:54

You grew up about 100 miles north of Wilmington?

David Cecelski 19:58

That’s right. I grew up in a little town called Havelock. I still have the family home-place there and I guess the family’s been there since the 1600s. We grew up very much in the world that the White supremacists of 1898 made. They were our heroes really. In fact, I had I had a book in my middle school classroom, I remember, that was focused on the 12 greatest North Carolinians. Ever.

Osha Davidson 20:24

The list included the Wright brothers, Virginia Dare, the first English baby born in what would become the United States of America, and…

David Cecelski 20:33

It had three of the 12 leaders of the White supremacist movement. In school no one ever told you about these things. It was just sort of the water in which we swam. Our streets were named after those people. In sports we played teams named after those people. There was nothing in our museums, no historical markers.

Osha Davidson 21:02

Some things have changed since the Cecelski’s childhood.

Promo 21:05

...the Cape Fear Museum of History and Science, in Wilmington is the state’s oldest History Museum. Initially, the museum was founded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to preserve the memory…

Osha Davidson 21:18

At the museum, I was pleasantly surprised to find a section devoted to 1898, including a short video documentary.

Documentary 21:25

Waddell fired all of the city’s Black employees and appointees. White Democrats led a campaign to banish African American leader from the city under the threat of death.

Osha Davidson 21:39

But change is painfully slow and uneven.

Osha Davidson 21:44

And I’m sorry, I didn’t get your name.

Shawn Jervay-Thatch 21:45

I’m Shawn Jervay-Thatch…

Osha Davidson 21:48

I was lucky to run into her. I was wandering around a quiet residential neighborhood in Wilmington on a Sunday afternoon trying to find the sight of Alexander Manly’s “Daily Record,” burned down by the White supremacists in 1898. Jervay-Thatch was locking up a small building that houses the Wilmington Journal, the city’s lone Black newspaper, where she just happened to be running a quick errand. But she knew where the Daily Record had been. She warned me there was nothing to see there. But she graciously agreed to walk me over to the site anyway.

Shawn Jervay-Thatch 22:22

So right here. I know it was right here.

Former site of the Wilmington “Daily Record.”

Osha Davidson 22:26

And this is just a grassy, gravelly parking lot now between a church and small house.

Shawn Jervay-Thatch 22:34

But it was right here.

Osha Davidson 22:36

Was there one incident, or…why did they do that?

Shawn Jervay-Thatch 22:40

Because basically the town was, the majority were African Americans: doctors, lawyers.

Osha Davidson 22:52

So, successful?

Shawn Jervay-Thatch 22:53

Right. And they didn’t like that.

Osha Davidson 22:56

And there’s nothing really to see here. There’s no…Is there a memorial or marker right here?

Shawn Jervay-Thatch 23:01

No.

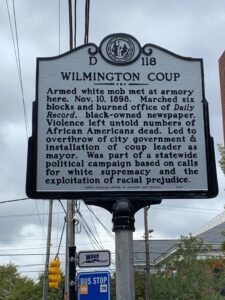

New sign marking the site of the Wilmington Coup of 1898.

Osha Davidson 23:02

A new marker did appear in November 2019. But not at the Daily Record. On a cold windy afternoon, some 200 people gather in downtown Wilmington. They stand huddled in a semi-circle outside the Light Infantry Building where the coup began a century earlier.

Deborah Dicks-Maxwell 23:25

(Reading names)

Osha Davidson 23:39

As the names of some of those killed that day are read, people bow their heads in prayer and remembrance. The reading doesn’t take long. No one knows the identities of all those killed. For more than 100 years, the events of 1898 were officially referred to as a race riot. But the new marker calls it what it was: a coup. Deborah Dicks-Maxwell, president of the local NAACP chapter, officiated at the ceremony. Maxwell explained why it took so long for Black people in the area to push for even this minimal kind of change.

Deborah Dicks-Maxwell 24:19

People need to understand where we’ve come from and understand that we are just highlighting this now, because the descendants of 1898, those survivors could not talk about it. In 1910, who could talk about this as a Black person?

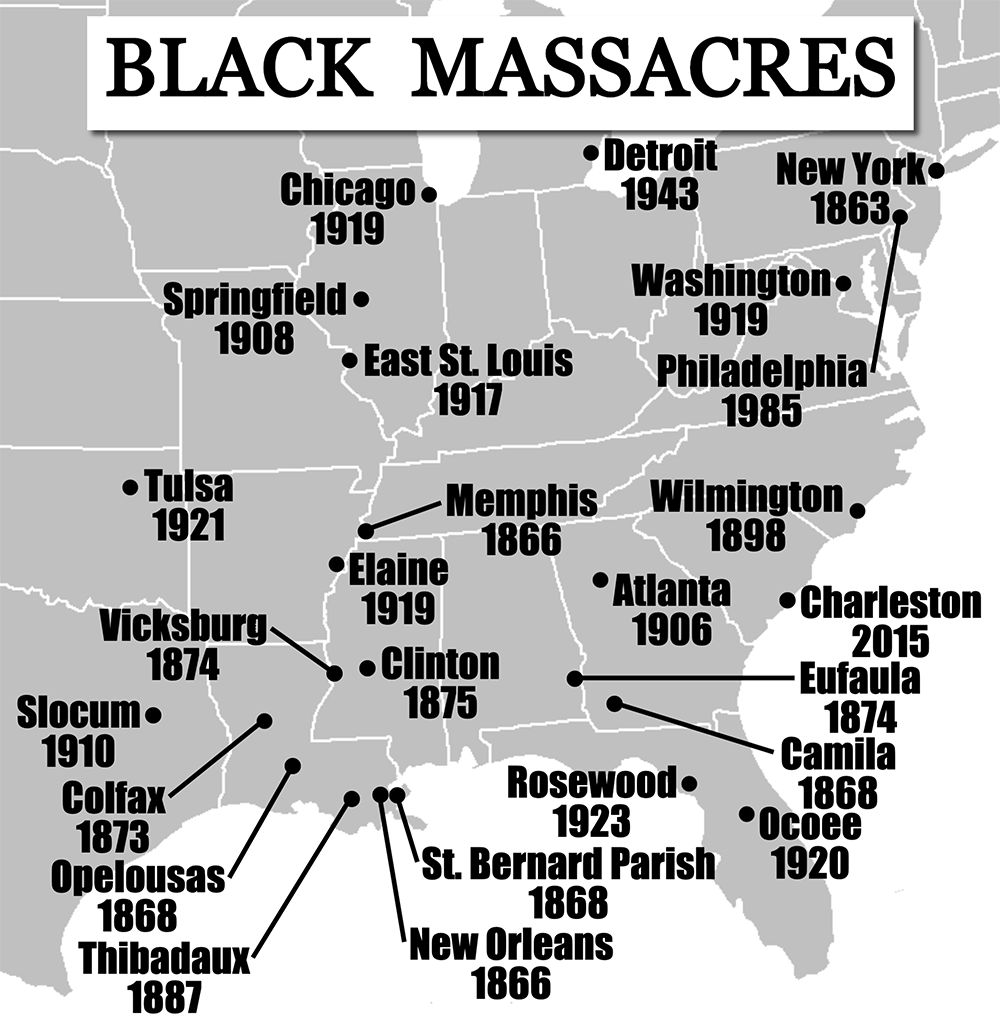

Osha Davidson 24:36

White society attempted to write the Wilmington coup out of American history books. But Wilmington is far from the only “disappeared” incident of mass violence perpetrated by White supremacists after the Civil War. The 1921 destruction of Greenwood, the prosperous Black section of Tulsa, Oklahoma, played a prominent role and not one but to HBO hit series: The Watchmen and Lovecraft Country. The Watchmen, winner of 11 Emmy Awards was set in Tulsa and the premiere began with the horrific destruction that left some 300 people dead, and dozens of square blocks burned to the ground.

Click here to go to updated map

Osha Davidson 25:26

These violent campaigns almost always had one thing in common. Their victims had become too successful, economically, politically, or socially. White supremacy has always rigged the system to prevent Black success. And when Black people have managed to overcome those hurdles, White supremacists have use brute force to punish that success. They did so in East St. Louis on July 2, 1917, killing at least 100 people.

Documentary 25:57

This Riot was probably the most brutal physically, you know, had the most staggering heinous physical things that they did, you know, to just take, go to a person and actually brutally shoot them, kill them, stone them, whatever. It’s, I don’t really know, I don’t have any. I can’t explain it.

Documentary 26:22

The fact that they had bodies hanging from light poles all through the business district of East St. Louis, I say that that haunts people’s imaginations, and I think it haunts that city to this day.

Osha Davidson 26:37

Those clips were from the 2018 documentary, “Always Remember.” Two summers later, in what became known as the Red Summer of 1919, White’s massacred Blacks by the hundreds in dozens of cities large and small, from Washington, DC, to Elaine, Arkansas, to Chicago, Illinois.

Claire Hartfield 26:57

There were some gangs some White immigrant gangs that had been waiting to foment violence.

Osha Davidson 27:03

That’s Claire Hartfield, author of the book, “A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riots of 1919.”

Claire Hartfield 27:11

And this was their moment. So they went to their club houses, they got their guns, they went into the Black community and from there, it just exploded.

Osha Davidson 27:19

Richard J. Daley, the Democratic mayor, who ruled Chicago with an iron fist for two decades, was a 17-year-old member of an Irish gang in 1919. He refused to confirm or deny that he took part in the five days of violence that left at least 38 people dead, hundreds injured, and more than 1,000 homeless.

Osha Davidson 27:50

Wilmington, Tulsa, East St. Louis, Chicago, Elaine, Arkansas, Rosewood, Florida, Columbia, Tennessee, Atlanta. The list of prospering Black communities destroyed by White supremacists during the era known as Jim Crow, is long. As is the willful neglect of this history. What Black Americans can never forget. White Americans are never taught. This ignorance of our past is why reparations seems unreasonable to so many Whites.

Mitch McConnell 28:23

Yeah, I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea. We’ve…

Osha Davidson 28:32

That’s Mitch McConnell, Republican senator from Kentucky and current senate majority leader, discounting the century of mass murder and lynchings that followed slavery, a deeply American history of violence that claimed an estimated 10,000 Black lives. Like Mitch McConnell, Wilmington resident George Rountree III is against reparations for the descendants of the Wilmington coup. Here’s Rountree interviewed last year on Wilmington WECT TV.

George Rountree 29:02

Now, suppose my grandfather was guilty of speeding. And he didn’t get a ticket. I mean, am I supposed to pay that ticket?

Osha Davidson 29:15

Rountree’s mention of his grandfather isn’t as hypothetical as it may sound. The first George Rountree, scion of a slave owning family, was a Harvard graduate and prominent Wilmington lawyer before the turn of the century. He was also the legal adviser to the coup leaders. The Rountree Family fortunes continued to grow after the coup. George the second, like his father, graduated from Harvard and then Harvard Law School before returning to join his father’s prospering law firm. His own son. George the third, joined the firm in 1962 and became senior partner in 1979. Inez Campbell-Eason works as a school psychologist. She also runs a small travel agency.

If the coup of 1898 hadn’t happened, it’s easy to imagine her attending one of the country’s most prestigious schools, like the Rountrees did. Her great-great-grandfather, Isham Quick, was a prominent Black businessman and real estate investor in Wilmington. He was also on the board of a Black owned savings and loan Association. The coup targeted Quick and most of his holdings were wiped out. Campbell-Eason is all-too-familiar with Rountree’s argument that White beneficiaries of the massacre owe nothing to the descendants of its victims.

Inez Campbell-Eason 30:37

That’s been the mantra of most White people, you know, since slavery ended. And it doesn’t matter that you weren’t there, you you were able to benefit. You know, your families were able to go to college, start businesses off of something that other people had built that was taken away. Yeah, it’s unfortunate that that 1898 occurred because it took away a legacy, you know, generational wealth in the city, not only for myself, but you know, so many others who remained.

Osha Davidson 31:10

Don’t expect to see reparations for descendants of the Wilmington coup anytime soon. Of the dozens of Black communities destroyed by White supremacists, only one has received any financial compensation. In 1994, 71 years after the Black hamlet of Rosewood, Florida was wiped out, the state of Florida paid $150,000 to each of the nine living survivors. Kirsten Mullen isn’t all that interested in Rosewood-style compensation. The co-author of the best-selling book, “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st century,” Mullen has spoken out before on this program against what she calls piecemeal reparations.

Kirsten Mullen 31:56

The whole part about the piecemeal effort is ultimately it’s a distraction if it takes our focus away from the wealth gap.

Osha Davidson 32:05

That wealth gap now means that for every dollar held by a typical White family, the typical Black family has just 10 cents. The only way to close this gap, says Mullen, is to enact a national program of reparations for American descendants of slavery. After visiting Wilmington, interviewing experts about it, reading about the catastrophe of 1898, and watching Christopher Everett’s excellent documentary, “Wilmington on fire,” I wondered, what the most important lessons are to be learned from the coup? I asked historian and author David Cecelski, what makes Wilmington different from earlier attacks on Black communities?

David Cecelski 32:45

It was future looking. It was a turning point because it laid the groundwork for Southern society and race relations into the 20th century, not by looking back by laying a violent foundation for the Jim Crow, apartheid-like one party social order that would unfold here in the early 20th century, and become the foundation for the quote unquote, modern South to come. For the modern and industrial South to come really. While keeping Blacks quote, unquote, in their place, repressing little “d” democracy, one party, limited democratic participation, scaled back voting rights and keeping power in the hands of business elites. So policies that were anti-union, low taxes, little social welfare. Basically, the South that came to be. And the South that, in my eyes, the rest of the US has come to emulate.

Osha Davidson 33:45

Christopher Everett gets the last word. He’s surprisingly optimistic about what we can learn from Wilmington. It’s a message that, to me, has a deep resonance to what’s occurring in America today.

Christopher Everett 33:58

We need to learn from it. And we need to learn what was working with all of us coming together and working together regardless of race and color. We all came together, you know, for one agenda. But we allowed certain entities to come in and break that up. And like I said, we still see those things going on today. And maybe we wouldn’t see these things going on if we would learn from our history. That’s what I think is important.

Osha Davidson 34:30

So many people helped with this episode of The American project. Thanks first to Christopher Everett. If you haven’t seen his documentary, “Wilmington on Fire,” you should definitely check it out. We’ll have a link in the transcript as well as links to all the books and other resources cited in this episode.

Thanks to David Cecelski. His book “Democracy Betrayed” is an excellent resource. Thanks also to Shawn Jervay-Thatch for showing me the site where Manly’s Daily Record once stood. We relied once again on the talented voice actor, George Webber. And, as always, profound thanks to Duke University Professor William “Sandy” Darity for serving as a consultant to this series. If you have questions or comments about this episode or the series itself, we want to hear them. You can email me at osha@TheAmericanproject.us or us or leave a comment on our website, www.TheAmericanProject.us.