Nothing exposes existing fissures in society like a catastrophe. The Coronavirus pandemic provides a tragic window into the effect of institutionalized racism on Black community health and how that’s related to the call for reparations.

Transcript

News anchor 00:00

…yesterday about the first death from the virus in Illinois, a woman in her 60s from Chicago. But that’s not all. She was a retired nurse with deep ties to her family and her faith.

Reporter 00:10

Patricia Friesen loved being a nurse in order to help people.

Narrator 00:18

This is Levittown, Pennsylvania, a new suburban community of 60,000 people midway between Philadelphia…

Levittowner 00:27

…very happy to buy a home here. But the whole trouble with this integration business is that in the end, it probably will end up with mixing socially. And you will have…Well, I think their aim as mixed marriages and becoming equal with a white.

Johnnie Mae Alston

You know, they’re telling you that you don’t belong on this side of town because of your race or whatever. And it’s not it’s not right, everybody wants a nice place. A nice home. Everybody wants to Same thing, but just because you think I would rather be here, or because I’m a certain race, you think that I should be over here. But what about my choices of where I want to live?

Osha Davidson 01:33

I’m Osha Gray Davidson, producer and host of “The American Project.” As much as podcasts can provide a distraction from difficult times, the fact is that we’re living in a pandemic. It feels irresponsible for me to ignore this context. So, first, these brief reminders: Practice physical distancing. Remember to wash your hands. Often. And do what you can to ease the suffering of others.

There’s also a more immediate link between the COVID19 pandemic and reparations. If you live in Chicago, you may have heard this story recently first death from the virus in Illinois.

News anchor 02:15

…a woman in her 60s from Chicago. But that’s not all. She was a retired nurse with deep ties to her family and her faith.

Reporter 02:23

Patricia Friesen loved being a nurse in order to help people. She also loved her family and singing to God. The 61-year-old Friesen died Monday after testing positive for the Coronavirus days earlier.

Patricia Frieson, Chicago.

Osha Davidson 02:38

It’s relevant to our topic that the first person to die from COVID19 in the state of Illinois was a Black woman on Chicago’s South Side. She was only 61 years old, but Friesen had a serious underlying condition that likely played a role in her death.

Reporter 02:55

…woman’s brother tonight. He said his sister went into the hospital on Thursday evening. She had bad asthma and they thought she had just had an asthma attack. Routinely every year she’d have to be hospitalized for her asthma once or twice a year.

Osha Davidson 03:10

Patricia Friesen suffered from severe and chronic asthma. That’s especially relevant in Chicago, where Black residents are 75% more likely to suffer from asthma than are white residents. But the problem isn’t limited to Chicago, or in fact, to asthma.

Osha Davidson 03:38

By now, you’ve surely heard that while the Coronavirus can infect anyone, the disease it causes, COVID19, is far more serious in people with underlying conditions. And if you’re like me, you may have heard that phrase over and over and then wondered, well wait, what specific underlying conditions are we talking about?

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the CDC, those conditions include lung disease, heart conditions, diabetes, and having a suppressed immune system. It is a tragic fact of life in America in 2020, that Black Americans are more likely to suffer from these underlying conditions than are whites.

Here are some statistics on this part of the nation’s racial health gap. Black women are 20% more likely than white women to have asthma. Black people in general are more likely to suffer from heart disease and 30% more likely to die from it. Blacks are also twice as likely as whites to have diabetes.

The other primary underlying condition is being immunocompromised. This can be caused by drugs given to transplant and cancer patients or directly from the disease AIDS, which makes sense because AIDS is an acronym for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

Dr. William L. Jeffries IV 05:04

African Americans continue to bear the greatest burden of HIV in the nation. It is the Black woman in her 30s and 40s…

Dr. William L. Jeffries IV, Associate Chief for Science in the Capacity Building Branch within CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention.

Osha Davidson 05:11

Dr. William L. Jeffries IV is an epidemiologist with the CDC in Atlanta. This is from a video Dr. Jeffrey’s made in 2013. But the most recent data shows that when it comes to AIDS, the gap between Black and white suffering remains just as troubling as the racial differences in the other conditions linked to COVID19 mortality.

While Black Americans account for 12% of the total US population, they account for a staggering 43% of diagnosed AIDS cases. The latest figures from the CDC showed that Black adults and adolescence were diagnosed with new cases of AIDS at a rate eight times higher than whites.

Some whites may have heard about these racial differences in health and maybe even felt sympathetic, but they’ve often attributed the differences to behavior. I asked Brian Smedley, the Executive Director of the National Collaborative for Health Equity, about the notion of “poor choices.”

Dr. Brian Smedley

Brian Smedley 06:12

It’s understandable that that view has come about. Again, this is the result of the broader negative narratives about people of color that are pervasive throughout our society. And it’s certainly true that there are some differences in health behavior, diet, attitudes, etc. Those differences in my view can be largely traced to both contemporary inequities in our history.

But to me, the determinant of health behaviors lies in our communities and in our neighborhoods. For example, when you take many metropolitan areas and the high levels of segregation that we see in most metro areas, people who live in majority communities of color typically are less likely to have access to a grocery store or a supermarket in their neighborhood. They’re less likely to have access to safe spaces for exercise or recreation. So in those circumstances, it’s important to understand that even though we may wag our fingers at folk who don’t adopt healthy behaviors, in some neighborhoods, those healthy behaviors are almost impossible to sustain.

Osha Davidson 07:17

And those segregated neighborhoods didn’t get that way by chance. No. They were created purposely by racial covenants that prohibited white homeowners from selling to Blacks, and by countless laws and government policies at the local, state and federal level, like programs that offered government backed low interest housing loans to white veterans after World War II, but not to Black ones. And when these measures didn’t work, whites have turned to other more direct methods.

Not to give away too much about future episodes, but I’m not including, not just yet, the out-and-out terrorism on a grand scale that whites inflicted on Blacks from the 1870s well into the 20th century. These mass killings happened throughout the South and the North for the crime of living where whites thought they shouldn’t, and even worse, for thriving there. For now, we’ll just go back to 1957 to the nation’s first planned suburban community.

Narrator08:24

This is Levittown, Pennsylvania, a new suburban community of 60,000 people midway between Philadelphia and Trenton, New Jersey, with this giant shopping center, and its winding lanes name for flowers and trees. It is fairly typical of communities all over America, where families are pursuing the American Dream to give their children a better chance in life.

Daisy and William Myers.

Osha Davidson 08:51

Just not all families are all children. This 1957 documentary looks at the initial reaction When a Black family headed by William and Daisy Myers bought the house at 43 Deep Green Lane in the Dogwood Hollow section of Levittown. This white woman’s reaction was typical.

Levittowner 09:12

…And we understood that it was going to be all white. We’re very happy to buy a home here. But the whole trouble with this integration business is that in the end, it probably will end up with mixing socially, and you will have…Well, I think their aim is mixed marriages and becoming equal with the whites…

Osha Davidson 09:33

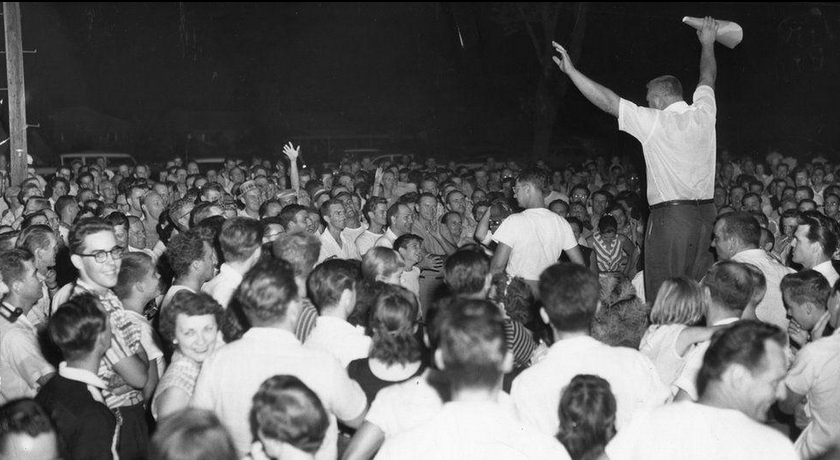

White discontent went quickly from open disapproval to individual threats of violence. Soon, large groups of white Levittetowners began gathering outside the Myers’ home at night. At first they shouted racial epithets and ordered the family to leave. When the situation escalated to stone throwing mobs, the governor called in the state police. That action likely prevented a full-on and potentially deadly attack on the one Black family in a “model community” of 60,000 people, a family who dared to break the whites only code.

Levittowners protesting the first Black family’s arrival into the all-white “model” suburban community, 1957.

Osha Davidson 10:19

Now this may all seem like ancient history. After all, the mob violence in Levittown happened 63 years ago. And the federal Fair Housing Act prohibiting segregation in housing was passed in 1968. But institutionalized racism still enforces segregation throughout America. The methods change, but not the reality for Black Americans.

Just last November, New York Newsday published the results of a landmark investigation three years in the making, into a hidden facet of racial discrimination and housing.

Narrator 10:57

Long Island is one of America’s most segregated suburbs. Newsday set out to discover what role real estate agents might play in keeping it that way, potentially affecting the quality of lives.

Osha Davidson 11:10

The newspaper shined a light on an illegal, but apparently common practice, called “steering.”

Robert Schwemm 11:16

Agents can steer through words. “I think you’d be more comfortable in this neighborhood” or “I think you’d be more comfortable in that neighborhood.”

Osha Davidson 11:24

That’s Robert Schwemm, a University of Kentucky College of Law professor and an expert on housing discrimination. Schwemm acted as an unpaid consultant to the Newsday investigation which conducted this interview.

Robert Schwemm 11:37

It can be done through actions without the prospects knowing it. I’m just giving the white prospect listings in a white area, I’m just giving the Black prospect listings in a Black area.

Osha Davidson 11:50

Nearly half of Black testers in the papers investigation were steered away from predominantly white communities. Here’s the very human reaction of one Black tester, Johnnie Mae Alston, talking about her experience.

Johnnie Mae Alston 12:04

…and putting you in a place that they think you belong. You know? They’re telling you that you don’t belong on this side of town because of your race or whatever. And it’s not right, because then you have no idea what’s out there until you look.

Everybody wants a nice place. A nice home. Everybody wants the same thing. But just because you think I would rather be here, or because I’m a certain race you think that I should be over here. But what about my choices of where I want to live? And I want to see as many places as anybody else see, so I can make a fair judgement on where I want to live.

Osha Davidson 13:03

We’ll post links to the Newsday story, the Levittown documentary, and much more in the online transcript at TheAmericanProject.us.

Segregation in housing is one important factor underlying any number of racial disparities that end up punishing Black Americans with poor health and poor health care, shorter lifespans, and less wealth. It also makes them more vulnerable to catastrophes.

There’s an old Black saying that uses physical health as a metaphor. When white folks catch a cold, Black people get pneumonia. The saying is used to describe things like economic downturns such as the 2007 recession.

But during the Coronavirus pandemic, it’s not just a metaphor. For millions of Black Americans today, it’s a harsh, and all too often, a fatal reality.

Osha Davidson 14:01

That’s it for this episode of The American Project. If you have comments or questions, you can leave them on our website, www.TheAmericanProject.us. Since we’re a podcast, feel free to respond verbally. That is: record your comment and send it by email to osha@theamericanproject.us. Who knows, we may play your recording, edited perhaps, on the air.

Remember to take care of yourself and your loved ones and your neighbors during this crisis. Stay healthy. Stay strong.

END

Links

Crisis in Levittown (documentary)

Newsday series on racial discrimination in housing: “Long Island Divided.”

The Coronavirus’s Unique Threat to the South (The Atlantic)