Many Americans believe the pursuit of reparations for slavery itself is a modern movement. While it is current, its origins extend back hundreds of years. Here’s just one example, dating back to 1865, three months after the end of the Civil War: A letter written by Jourdon Anderson, only recently freed, to his former “master.” The slaveholder had contacted Anderson, asking him to return to work for pay.

Anderson’s reply is priceless (forgive the pun), and a reminder that Black Americans who had been held in bondage expected not just freedom, but restitution for their years of unpaid labor — an expectation their descendants have not abandoned.

LETTER FROM A FREEDMAN TO HIS OLD MASTER (1865)

Dayton, Ohio, August 7, 1865.

To my old Master, Colonel P. H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee.

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the[266] folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson

Transcript

In this wide-ranging conversation, prize-winning economist William Darity, Jr. (Sandy) discusses his plan for reparations for American slavery and its legacy. Based on thirty years of research, Professor Darity’s plan is pragmatic, at once fiscally sound and deeply moral.

He is co-author, with A. Kirsten Mullen, of the just-published book: “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century,” which has been hailed as “a vital intellectual history and a roadmap for these times.”

William Darity, Jr. 00:07

The directive that Sherman issued in 1865 provided a significant swath of land stretching from South Carolina to northern Florida along the coastal zone that was to be assigned to the formerly enslaved as 40-acre land grants. Had those grants been made and had the freedmen had an opportunity to preserve their access to those lands we probably would not be having a conversation about reparations in 2019.

William Darity, Jr. 00:46

When we start looking at wealth, I mean the magnitude of the disparities or inequality, they’re so great that I think that frequently when people talk about various kinds of mechanisms or approaches to closing the racial wealth gap, they don’t fully understand how large it is. If you were to look at the full gap, then we’re talking about a differential per household in the vicinity of $800,000.

William Darity, Jr. 01:18

At the fundamental level, I think it is a statement about whether or not the principles that we all typically say and form the existence of this nation, what Gunnar Myrdal referred to as the American creed, the decision this nation makes about reparations will dictate whether or not there’s any prospect for the American creed being valid.

Osha Davidson 01:51

That’s prize-winning economist William “Sandy” Darity, a professor at Duke University and today’s guest on The American Project. I’m Osha Gray Davidson, producer and host of the program. Back in the 1980s, Professor Darity was asked to write an introduction to a book about reparations for slavery. He declined explaining that it was an idea going nowhere. But three decades later, the former skeptic is widely considered the leading intellectual of today’s reparations movement. During the Democratic primary, several of the leading candidates sought his advice on the issue.

Professor Darity is the co-author of “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century.” The book was just published by the University of North Carolina Press and has been lauded as a roadmap for our times. Our far-ranging conversation was recorded in late 2019, and we had a follow-up interview by phone just last week.

I began by asking Professor Darity about his first exposure to the concept of reparations.

William Darity, Jr. 03:02

So, I’m not certain when I first encountered the idea of reparations. I am better able to remember when I first made a commitment to trying to do the work that would support reparations for Black descendants of folks who were enslaved in the United States. So that was toward the end of the 1980s, beginning of the 1990s. Specifically, a scholar at based at the University of Pennsylvania, Richard America, asked me to write the introduction to a volume that he was editing that subsequently has been called “The Wealth of Races.” I think it was published around 1991. But Richard had assembled a set of essays primarily by economists that attempted to estimate what the magnitude of a reparations bill should be. And he asked me if I would write the opening essay for the volume based upon the, the articles that he had put together.

And my initial reaction was, well, you know, I think reparations is something that’s a good idea as a matter of principle, but it’s never going to happen. And I have no idea how logistically, it would actually be engineered. And so, I think I had kind of the reflexive reaction that many people still have today. But I went through the process of reading the essays because he convinced me that I should write the introduction, regardless of what I concluded, and I went through the process of reading the passages and the more that I read, the more convinced I was that the task of achieving reparations was something that had to be pursued even if it seemed to be extremely difficult to bring about So, I think that was the point at which I made the commitment to trying to do the work that would support a reparations effort.

Osha Davidson 05:08

Tell me when and how did the idea of reparations begin. It isn’t a new idea is it?

William Darity, Jr. 05:15

In the U.S. context, the notion of reparations is something that evolved during the course of the period of enslavement. And it evolved to such a degree that at the point of emancipation, there was a well-founded expectation on the part of the formerly enslaved that they would receive 40-acre land grants as restitution for the historical injustice that they had been subjected to and to give them an opportunity to participate fully in American economic life. So, I would date the origins of the claim or cry for reparations to at least the period of the 1820s, if not earlier, when folks were talking about this notion that when slavery ended, there should be some form of compensation for the folks who were subjected to enslavement.

Osha Davidson 06:17

When I was doing research, I saw that in 1774, so, two years before the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Paine wrote a pamphlet titled “African Slavery in America,” in which he called for the abolition of slavery, saying it was wicked and inhumane.

Thomas Paine

And he wrote, “The Great question may be what should be done with those who are enslaved already? Perhaps some could give them lands upon reasonable rent. Some employing them and their labor still might give them some reasonable allowances for it. So as all may have some property and fruits of their labors at their own disposal.” So, what are your thoughts about that, when that was in 1774 before the U.S. was the U.S.?

William Darity, Jr. 07:01

That’s a great find and I wasn’t aware of that. That’s fascinating. Well, I think it what it reinforces is the idea that not everyone believed that slavery was the right thing to do. So, you know, frequently we hear kind of a dismissive observation when you complain about historical injustice is something to the effect of, well, that’s what everybody thought back then. So, it’s unfair to impugn any individual who was an advocate of slavery. And I think the…

Osha Davidson 07:38

…Right, the old argument of they were a person of their times.

William Darity, Jr. 07:42

That’s right. And so, you know, the Thomas Paine statement makes it clear that not every person was a person of that time. So, I think that’s part of the significance but I’m also truly intrigued by the fact that he was already anticipating the value of having some form of reparations program for the folks who had been enslaved.

Osha Davidson 08:06

One of the more important dates in this is later. Can you talk a bit about the significance of Sherman’s field orders 15, where I believe the phrase 40 acres and the mule part, where that began.

William Darity, Jr. 08:21

So, there’s actually no mention of the mule in General Sherman’s Special Orders number 15. But that’s the directive that Sherman issued in January 1865, which is actually before the war actually ended. That’s the directive that Sherman issued in 1865 that provided a significant swath of land stretching from South Carolina to northern Florida along the coastal zone that was to be assigned to the formerly enslaved as 40-acre land grants. And so that was the initial push to do that. And the process actually got underway. I believe about 40,000 persons were settled on 400,000 acres of land in a very short span of time. But, that process was reversed and the lands restored to the former slaveholders by order of President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor.

Osha Davidson 09:32

How significant would it have been had Sherman’s plan not been stopped from going into effect by President Andrew Johnson? I mean, would we be talking about reparations now?

William Darity, Jr. 09:43

We may not be. I mean, it’s certainly a matter for speculative fiction. But I think that had those grants been made and had the freedmen had an opportunity to preserve their access to those lands, which would have required an extended presence of the Union Army and or arming the freedmen themselves, had they been able to preserve their property we probably would not be having a conversation about reparations in 2019. And if we think about the full scope of what was envisioned, not exclusively by Sherman, but primarily by members of the republican party like Thaddeus Stevens, if the 40 acres had been extended across the entire enslaved population, that would have meant at least 40 million acres of land would have been allocated to the freedmen. And this would have been done across large portions of the South, particularly because it would have required the use of abandoned lands or abandoned properties that formerly had been held by the slaveholders. And I think we would then have a very different set of prospects for the economic future of Black Americans who had been subjected to slavery.

Osha Davidson 11:08

Just one more question about Johnson. I know he thought that the descendants of slavery needed to advance but adamantly believed that the relative position of Blacks and whites must remain the same. And I wonder, don’t we live in a world that’s pretty much as Johnson envisioned, that he in fact, helped design?

Sandy Darity 11:28

“From Here to Equality,” co-authors, William Darity, Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen.

Yeah. And in fact, it’s interesting that you say that, because one of the points that Kirsten Mullen and I make in our book is that Johnson actually does advocate additional education for the formerly enslaved. But he argues that it’s necessary to have even higher degrees or more advanced education for whites so that you can maintain the relative distance between the two communities. And I think that’s precisely the kind of world that we’re in today, where relative differences between Blacks and whites remained fairly stable over long periods of time.

I mean, you could argue, in fact that since the passage of the Civil Rights acts, there’s actually been no significant change in the relative position between Blacks and whites on a number of indicators, whether it’s the unemployment rate, whether it’s family income, whether it’s the degree of educational attainment that’s associated with higher education. And beyond that, there’s been not much of a change in the relative position or the comparative position of Blacks and whites. I think that the unemployment rate is a very stark indicator of this. You know, the current president has touted this notion that the Black unemployment rate is at a historic low, a low that has never been attained since we have been required unemployment statistics by race. And that may be true. But what is also true is that the Black unemployment rate is still two times as high as the white unemployment rate, which has been a statistical regularity ever since we began to collect unemployment statistics on the basis of race.

Osha Davidson 13:23

That brings us to what seems to be a really important and perhaps central theme, which is the wealth gap. Could you talk about that? Because I was I was surprised when I read the extent of it and how pernicious it is.

William Darity, Jr. 13:37

So, the wealth gap actually is a condition that might be worse now than it was 50 years ago. So, there’s some complications over how we could estimate what the wealth gap was in the mid-1960s. But to the extent that people have attempted to do it we could, we could clearly see that the wealth differential appears to be wider today than it was some 50 years ago. So, that’s a case in which the comparative position does not remain the same. If anything, it’s worsened. And it’s worsened to such a degree that as of 2016 if you look at the data from the survey of consumer finances, if you were looking to look at the middle Black family and the middle white family, you would have a differential of net worth of about $154,000, where the median Black family would have a net worth of about $17,600, and the median white family would be at about $171,000. So, there’s a very sharp difference that’s reflected by looking at the most typical Black and white households in terms of net worth.

“I don’t think reparations is a casual option. It’s been a long time coming. But that doesn’t make it any less compelling.”

— Sandy Darity

On the other hand, if you were to look at the full gap that would be represented by the difference in the mean values of wealth between Blacks and whites, then we’re talking about a differential per household in the vicinity of $800,000. So, these are immense differences. Another way to think about it is Black Americans constitute about 13% of the United States population but hold or own less than 3% of the nation’s wealth. Whites, in contrast, are approximately 75% of the nation’s population and own upwards of 90% of the nation’s wealth. So, there’s a sharp differential in terms of the proportionate shares and the proportionate share that’s held by Black Americans is grossly inconsistent with the Black share of the nation’s population.

Osha Davidson 16:02

And that’s overall. What happens to the wealth gap as you get closer to the poverty line?

William Darity, Jr. 16:09

So, there’s sharp racial differences in the wealth gap, even at lower levels of income. So, the poorest whites, whites who are in the lowest 20% of the income distribution, actually have a higher average level of wealth than all Black Americans taken collectively. So, when we start looking at wealth, I mean, the magnitude of the disparities or inequality, they’re so great that I think that frequently when people talk about various kinds of mechanisms or approaches to closing the racial wealth gap, they don’t fully understand how large it is and how dramatic the kinds of policy interventions would have to be to actually eliminate those kinds of disparities in full.

Osha Davidson 17:03

So, what should a well-designed program of reparations include?

William Darity, Jr. 17:08

So, I’ve been thinking increasingly that there are two major elements that should be components of a well-designed reparations program. The first is a component that builds Black assets in such a way that we eliminate the racial wealth gap.

The second component has to do with a project of changing the nation’s historical memory, particularly with respect to the period of reconstruction and the civil war itself. I think that what’s happened in the United States is the national memory has been captured by the Confederate sympathizers with Confederate allies who were still around today. One of the most important organizations that has promoted the way in which we think about the Civil War and Reconstruction and has promoted in a false and inaccurate way of thinking about the Civil War and Reconstruction is the United Daughters of the Confederacy. What the net effect has been is to treat the Confederate cause and the Confederate leaders as heroic actors or as a heroic action, when in fact, the Confederate cause was an active traitorship and the Confederate leadership were individuals who were traitors to the United States. And so I think we have to reconfigure the story to make it more accurate, more precise, and to make the nation’s historical memory consistent with the nation’s actual historical experience.

Osha Davidson 18:42

So, you’re talking about an educational program?

William Darity, Jr. 18:45

Yes, it’s an educational program or an educational facet of a reparations program that would be comparable or similar to what was built into the legislation to provide reparations for Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during the course of World War II, unjustly incarcerated in the United States. So, one facet of the Japanese reparations program was a series of direct compensatory payments that were made to folks who had been had been victimized by that imprisonment process. But a second aspect of the legislation was a set of provisions that were intended to institute curricular and instructional programs that would provide young Americans in particular with substantial knowledge about what happened in World War II to Japanese Americans. I think one of the unfortunate aspects of that is the funding that was supposed to be provided for that dimension of the Japanese American reparations project, the funding was never given in full. And so that type of memory remedying practice was never was never activated as substantially as it should have been. But I think that that needs to be a component of a reparations program for Black American descendants of persons who were enslaved here. And it’s an important component and it needs to be appropriately funded and supported as well.

Osha Davidson

I wanted to ask you about the time period that claims for reparations covers. I think I’ve read that you’ve said that reparations for slavery should cover the period from 1776 forward, not 1619 when the first enslaved Africans arrived. Why?

William Darity, Jr. 20:43

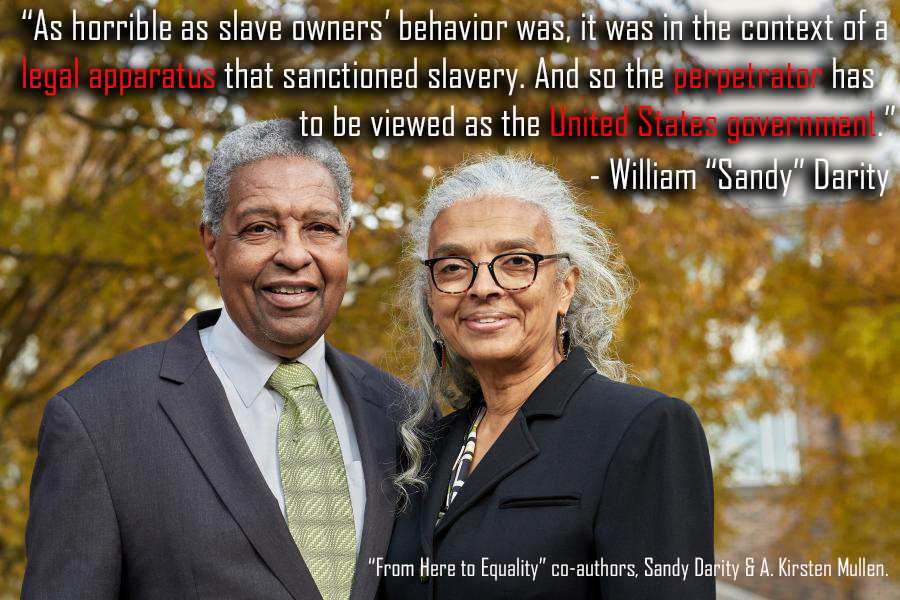

Because I think that the relevant perpetrator of the atrocities that are associated with the full historical trajectory of injustices that have been inflicted on Black Americans who were either enslaved themselves, or their descendants, must center on the United States of America, on the U.S. government. The U.S. government is the critical perpetrator. And that is primarily because it is the U.S. government that maintained the legal and authority structure that made this array of atrocities that stretch from the period of enslavement through legal segregation in the United States, the Jim Crow period, into the present moment in which we have mass incarceration, we have police killings of unarmed Blacks, we have sustained and ongoing discrimination in employment, and we have, as I mentioned earlier, this enormous racial wealth gap.

All of these things are a consequence of an array of policies that have been adopted by the United States government or the government’s failure to prosecute acts of murder that have been conducted by white Americans directed at Black Americans on racial grounds. So, to the extent that the United States government bears responsibility, it’s a national responsibility, then that’s who should be the appropriate target for a reparations claim. And that claim has to be anchored on the United States as an existing national unit. And that existence does not begin until 1776. So, I’m not somebody who says the claim that should be made for reparations should extend to 1619. Not if the claim is being made on the United States government. Otherwise, I think you have to look at a host of countries that are engaged in settler-colonialism here. And I think that that’s something that’s beyond the ken of my personal my personal research purview for thinking about how best to construct a reparations program. But if somebody else wants to go that route, I welcome them to do that. But in the work that I’ve done, the focus has been on a reparations claim that must be made towards the United States government.

Osha Davidson 23:13

That leads to a question that I encounter a lot. And that’s who receives reparations from the United States government. There seems to be a split between American descendants of slavery and people who say that, well, no, since reparations covers more than just slavery itself, then, reparation payments should be made to people who are not descendants of slavery here, but maybe in Haiti or Jamaica, and then then moved here. Can you talk about that?

William Darity, Jr. 23:49

Yeah, I’ll try to talk about the question of who should be eligible. So, let me make a first sort between persons who should be eligible who are Black and white, because there clearly are some white Americans who have ancestors who were enslaved in the United States. But because these individuals have been living as white and have benefited from the social advantages associated with whiteness, I don’t think they should be eligible for reparations.

So, one piece of the divide in terms of determining eligibility is a boundary that we might need to establish between who is Black and who is white. But then the second boundary has to do with the question of who among individuals who are Black in the United States should be recipients of reparations from the United States government. And again, I want to emphasize that my focus is on the notion that the United States government is the perpetrator and so in that case, it is only individuals who are descendants of folks who were enslaved in the United States who have a claim on the U.S. government that is anchored in the denial of the 40 acres to their ancestors. So, that’s the first dimension of it.

The second dimension is that that’s the only community that has had to endure all three phases of atrocities. The first atrocity being associated with slavery, the second atrocity being associated with the Jim Crow period, and the third set of atrocities being associated with the harms and damages that have occurred in the post-civil rights legislation era. And so there’s only one community that has had to experience all of that and had to bear the burden of the cumulative effects of all that. And those are individuals who are descendants of persons who were enslaved in the United States.

But then the third point that comes to mind is that there’s a very complicated set of questions that are associated with folks who have made the decision to migrate to a country that engages in racist practices, but then turn around and ask for reparations from that country, when you know that it was quite obvious that there was some decision that was made, that the benefits of coming here outweighed the potential harms. Now, whether or not that judgment was made accurately or not, I can’t say, but I can’t imagine my making a legitimate claim if I move to a totalitarian country, knowingly moved to a totalitarian country, I can’t imagine how I could make a legitimate claim for reparations about the totalitarian practices of that country. I might well be heavily engaged in efforts to try to alter the conditions there, but I don’t know about making a reparations claim.

And then the final point, I’d like to make about the question of compensation for Blacks who are more recent immigrants to the United States is that I do, in fact think that virtually all of them do have a claim for reparations. But that claim is not something that should be directed at the United States government. It should be directed at the various countries or array of countries that enslaved or colonized their countries of origin. And we know that there’s actually an initiative that’s been undertaken by some of the Caribbean countries under the umbrella of the CARICOM commission for reparations. That Commission has directed its claims for reparations to primarily the United Kingdom and to France, because those are perhaps the most significant colonial powers that have had an impact on the fates of the individuals who are in the countries that formed that commission.

In point of fact, that commission has not made any overtures to include the claims of Black Americans in this process, and nor should it. But I think it’s indicative of the fact that although there is a sense of solidarity and commonality of purpose across Blacks in the full diaspora, there are specific and unique kinds of claims that each community of Black people should make, have to make, and need to make.

Osha Davidson 28:42

You’re listening to The American Project, combining interviews with leading experts with archival recordings to explore some of the most vital issues facing the United States, a democracy in the works. If you value the program, please consider subscribing.

Today we’re talking with William “Sandy” Darity. He’s the Samuel Dubois Cooke Professor of Public Policy, African and African American Studies and economics at Duke University. Professor Darity also directs the Samuel Dubois Cooke Center on Social Equality at Duke and is co-author with A. Kirsten Mullen of a landmark book: “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century.” Most of our discussion was recorded in late 2019, but I recently checked in with Professor Darity. He believes how our government is dealing with the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic holds important lessons for funding reparations.

William Darity, Jr. 29:42

I think the coronavirus crisis itself makes it evident that the government has a phenomenal capacity to engage in expenditure. You know, virtually overnight, the government came up with $2.2 trillion and I believe that the amount of funding that is going to go towards at least allegedly supporting people’s incomes in this time of crisis, it’s going to be as much as $5.5 trillion. And so the current crisis actually provides a demonstration point for the capacity of the federal government to spend. And I want to add the federal spending, because the federal government has a sovereign currency, is not tax constrained. That is to say the government does not have to acquire additional taxes to engage in additional spending. And in fact, you could argue that the federal government has an unlimited capacity to spend. The only barrier is the inflation risk. And that’s something that would have to be managed in the context of any expenditure program, whether it’s reparations or it’s for something else.

So, I would argue that a well-designed reparations program in the zone of $10-$12 trillion could be financed readily without raising new taxes. It would have to be performed by increasing the deficit, but there’s nothing really bad about the deficit in-and-of itself, as long as a higher deficit does not constitute a higher government debt. And you don’t have to finance government expenditure by taking on additional debt.

So, how would you control the inflation risk with a program of reparations for Black American descendants of U.S. slavery? Well, one thing you could do is space the payments out. So, you could set up a target to eliminate the racial wealth gap over the course of a decade, a 10-year target. And in the process, then, you could spread the payments out so that the impact in any individual year would not be as pronounced. Secondly, the payments can be made in a form that are less liquid assets. That is to say you could distribute the payment to eliminate the racial wealth gap in such a way that you’re not giving people money that they can immediately spend.

So, let me give an illustration. We could give people endowments, say they were $200,000 endowments. We might allow them to spend the interest off of that endowment in any given year, which at least initially would amount to about $10,000. Then after that, people could apply to spend portions of the principle under special conditions to an agency that might make judgment over whether or not it was it was permissible for them to do so. So that’s a way in which you could give people additional spending power through the reparations program, but you could also ensure that you increase their level of wealth. A final possibility is to minimize their need to spend on basics or even some luxury items by having a wider array of social policies that protects everybody’s income. And here I would include having a national health insurance program and having a federal job guarantee.

Osha Davidson 33:15

Now back to our earlier discussion recorded, thankfully, in a studio. When I talk to people, particularly white people, about reparations, their objections are pretty much summed up by what Senator Mitch McConnell said.

Mitch McConnell 33:32

Osha Davidson 33:41

How do you address, I mean, do you come across those and how do you address those objections?

“As horrendous as [slave owners’] behavior was, it was in the context of a legal apparatus that sanctioned slavery. And so the perpetrator has to be viewed as the United States government.”

— Sandy Darity

William Darity, Jr. 33:47

Well, yes, I come across that argument that the individuals who were perpetrators are gone and their direct victims are all gone, and so you know, we don’t have any obligation to construct a reparations program for the folks or their descendants. Yeah, I mean, I hear this routinely. The first thing I want to argue is that as horrendous as the behavior of the slave owners was on so many dimensions, I mean, I think it’s quite clear that we can talk about their actions as constituting a set of atrocities, okay? As horrendous as their behavior was, it was in the context of a legal apparatus that sanctioned slavery. And so the perpetrator again has to be viewed as the United States government and the United States government still exists. It is still the same constitutional entity that it was in 1776.

So, it becomes irrelevant that the slave holders are, that the original slave holders are dead. Now what about the question of the status of their direct victims and the fact that they are no longer living? Well, I think that had the provision of 40 acres been made then there would not necessarily be a sustained inter-generational claim for restitution. But that restitution was not made, and so the descendants still have a claim based upon the failure to provide compensation for the years of slavery to their ancestors. Plus, there’s a host of ramifications across generations from the deprivation of access to what essentially would have been a body of wealth that would have been embodied in land.

But, moreover, people like Mitch McConnell, particularly in his age range, very much alive during the years of Jim Crow and continue to be very much alive in the period in which we are encountering mass incarceration, we’re encountering police executions of unarmed Blacks, and the like. All of these things are happening in real time and are happening to living descendants of the persons who were enslaved in the United States. So, you know, my inclination is to think that this is a deflective argument that misses the point, but it is widely used.

Osha Davidson 36:26

And I know it’s tempting to see the debate in purely ideological terms, but one of the strongest white supporters of reparations was the conservative pundit, Charles Krauthammer. I was surprised that in 1990, he wrote in “Time” magazine, “Forget the crumbs, demand reparations.” So, is it possible do you think to champion reparations from a conservative standpoint?

William Darity, Jr. 36:51

Well, yes, I mean, I think it is possible to champion reparations from a conservative standpoint. I think that the reason resistance to reparations is something that is held by people who are both typically labeled as being conservative or liberal. I mean, if we’re talking about a condition in which approximately 20% of white Americans say that they endorse reparations for Black Americans, that 80% that has not made that kind of commitment is going to include people who we would we would identify as both liberal and conservative. But I think that among those folks who support reparations, the rationale might be somewhat different for persons who see themselves as being conservatives and persons who see themselves as being liberal. And if I’m thinking specifically about Krauthammer, his argument, I think Krauthammer was arguing in favor of a reparations program as a means of eliminating affirmative action. And so that’s the trade-off he was he was willing to make. And, you know, there are moments in which I feel like I’m willing to make the same trade off if the amount of the reparations payments is sufficiently high.

Osha Davidson 38:11

So, let’s get to that. what’s the amount that would be sufficient?

William Darity, Jr. 38:15

Well, the baseline amount that would have to be given for us to think that — and when I say us, those of us who are engaged in the in the reparations project — I think that the baseline amount that would have to be delivered that would make it reasonable to say, okay, that’s an amount that meets the bill, is an amount that would actually eliminate the racial wealth gap. That’s something in the vicinity of $10-$12 trillion. I’ve seen higher estimates, you know, of what the bill should be than that. But I think that that’s the, if we’re, if we’re going to start talking about what’s a reasonable number in terms of compensation for the full scope of these of these atrocities, how do we manage to address the cumulative effects of these various atrocities, then I think we have to look at the racial wealth disparity. And that’s where we should set up our starting point for determining what the compensation should be.

Osha Davidson 39:25

And that’s the point — the objections that I hear from liberals in particular, who say, yeah, reparations may be a good idea in principle and theory, it’s moral, but it’s not practical. That it would effectively break the bank.

William Darity, Jr. 39:40

Well, so the argument that you know, that…This is another obstructionist question that people raise when they always say, Well, how will you pay for it? So, you know, there’d be virtually no positive social program we could we could enact in the United States if we stayed stuck on the question of how will you pay for it. I’ve come to really dislike the question of how you pay for it. Folks don’t ask that about military budgets. But they do ask it about any other kinds of transformative social programs.

Osha Davidson 40:17

Yeah, with a military budget I guess they say, well, it’s something we just have to afford. And with reparations, for a lot of people they just think, well, it’s not something we have to do. And yet it doesn’t seem like this nation can move forward without doing something about this huge wealth gap that causes enormous problems on all sorts of fronts. And not solely, mainly for Black Americans, but not solely.

William Darity, Jr. 40:46

I don’t think reparations is a casual option. It’s been a long time coming. But that doesn’t make it any less compelling. And so to the extent that people say that national defense is something that’s vital, I think that the national moral status or standard is also something that’s vital. And the immorality of the treatment, the historical treatment of Black people in the United States is something that has never actually been addressed. And so I think it’s just as vital to the national well-being for that to be something that is actually taken up.

Texas Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, primary sponsor of HR 40, calling for a Congressional Commission to consider reparations. (June 19, 2019)

Osha Davidson 41:29

I do want to come back to that. I did want to ask, though, about HR 40. Some supporters of reparations have spoken against HR 40, saying that calling for a study is an example of paralysis by analysis. And isn’t that a real danger that a study will be a substitute for action instead of…

William Darity, Jr. 41:50

…it’s always possible that if you form a study commission it can produce a report that is not satisfactory. That’s going to be contingent upon whom is assigned to serve on the commission. And it will also depend in large measure upon who are the individuals who are identified as the chairs and co-chairs of the commission who would have a leadership role in dictating what the content of the study would be. On the other hand, I think it is important that this is a step that’s taken. As a prelude to the Japanese American reparations program there was a congressional commission, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, that produced a report that accomplished two things. First was, it set the historical record straight. It established that the United States officialdom knew that the Japanese American community was not a national security threat but still proceeded to have them incarcerated in camps around the country. That was a critical piece of information that made it unequivocal that the incarceration was unjustified and unjust.

Some of the 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry being shipped to internment camps, 1942. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan made a formal apology and signed the Civil Liberties Act, paying reparations to those who had been interned.

But the second thing that that report did was it provided a plan of action for restitution. And so I think that there’s a need for a parallel type of commission that would be a prelude to a reparations program. And I especially think it would be important if we in fact generated a high-quality report from this process. It would be important from the standpoint of actually moving national opinion in the direction of further support for a reparations program. I mean, clearly to have any significant opportunity of having a reparations program enacted we probably have to at least double the proportion of white Americans who are in support of a reparations program. And I think that that doubling would become more possible if we had a national commission, a congressional commission or a presidential commission, that generated a report that indicated precisely why a reparations program is essential, and also detailed how a reparations program might actually be executed.

Osha Davidson 44:22

So, would this be part of the educational program that you were talking about in a way?

William Darity, Jr. 44:27

In a way, because, you know, it’s not exactly what I was talking about, because the commission would not be executing the reparations program itself directly. And so there would still need to be a deep instructional educational component to the actual reparations program, and it would have to be funded in part by the entire structure of support for the reparations program. But, yes, I think that the commission’s report could serve a vital educational function. I must say, I think that HR 40, as it’s currently written is not adequate. I think it needs to be revised.

Osha Davidson 45:17

In what way?

William Darity, Jr. 45:18

I think that there needs to be greater specificity about what types of tasks the commission should undertake in terms of its responsibilities with respect to establishing the historical record, with respect to its responsibilities in terms of design of the reparations program. We talked a bit earlier about folks who have tried to anchor the starting point for Reparations claim at 1619. But since this is legislation that would be specific to the United States of America as a governmental entity then I think it needs to be worded in such a way that 1776 is the starting point. I think the current version of the legislation talks about 1619 also. So, there’s a number of changes that I think are needed. There needs to be a timetable that’s built into the legislation, a timetable that is adequate for the commission to do its work, but also a timetable that precludes the commission going on indefinitely without actually generating a report. So there are some logistical and there are also some issues that are, I guess, a bit more philosophical. There are some inaccuracies in the legislation. For example, I think at some point in HR 40 it says something about there being 4 million people who had been enslaved in the United States. That’s not accurate. It’s more than 4 million who actually were who actually experienced enslavement in the United States. There were 4 million enslaved persons at the point of Emancipation. But the total number of people who actually were enslaved between 1776 and 1865 was larger than 4 million people.

Osha Davidson 47:11

How optimistic are you that an effective reparations program will be adopted?

William Darity, Jr. 47:17

So, it’s 150 years and counting. And so given that it’s been that long period of time, and the demand is so, so just and valid, you know, I guess I don’t want to have an expectation that this will necessarily happen in the next few years, or perhaps even within my own lifetime. But I don’t think the demand is going to is going to vanish, because it’s completely valid. So, let me let me say this about my degree of optimism. I think I’m more optimistic at this moment than I ever have been simply because the level of discussion and conversation has entered into the highest orbit of the political arena that exists in the United States. And so, you know, I don’t know what’s actually going to happen. But I find the present moment to be somewhat promising.

Osha Davidson 48:26

Well, let me go back to what we were talking about, about the moral implications. What do you think it says about the United States at a fundamental level how we ended up dealing with the issue of reparations?

William Darity, Jr. 48:39

At the fundamental level, I think it is a statement about whether or not the principles that we all typically say inform the existence of this nation, what Gunnar Myrdal referred to as the American creed. The decision this nation makes about reparations will dictate whether or not there’s any prospect for the American creed being valid.

Osha Davidson 49:07

Okay, well, is there anything else that you’d like to say or talk about that we didn’t cover?

William Darity, Jr. 49:12

I want to reemphasize this notion that the claim for reparations is not a claim that’s exclusively directed at slavery, that slavery is the crucible for the creation of a society that’s been deeply anchored in white supremacy and has consistently damaged and stunted the lives of Black Americans, but, it is not slavery alone that is the basis for reparations claim. It must also include two other phases in American history. The second phase is the period of legal segregation, or what we refer to colloquially as the Jim Crow period, almost lasted a full century, and then the period after the passage of civil rights legislation in which we still have a sustained array of atrocities that are directed against Black Americans. And so I think it’s important when we start talking about the bill of particulars as the rationale for reparations that we take into account all three phases of American history. And we have to pay attention to the full effect of all three phases on Black descendants of persons who were enslaved in the United States.

Osha Davidson 50:34

Professor Darity, thank you so much for talking with us today.

William Darity, Jr. 50:37

Thank you for having me.

Osha Davidson 50:44

That’s William Darity, Jr., the Samuel Dubois Cooke Professor of Public Policy, African and African American Studies and economics at Duke University. Professor Darity also directs the Samuel Dubois Cooke Center on Social Equity at Duke. He’s the co-author along with A. Kirsten Mullen of the book, “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century,” published in March by the University of North Carolina Press. We’ll include a link to the book in the transcript of today’s episode. If you have a question or comment about anything on our podcast or something we should have included but didn’t, we want to hear from you. Go to our website, www.TheAmericanProject.us, or us. Or you can always record your thoughts and send them by email to osha@TheAmericanProject.us. And please subscribe to our podcast in iTunes, Google Play, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.