The history of America’s elite schools is the history of slavery. We look at how Georgetown and Brown Universities are trying to come to terms with their long-hidden origins. Guests include NYT reporter Rachel Swarns who broke the Georgetown story in 2016.

Transcript

American Universities & Slavery

Jim Wickman 00:02

Good morning. My name is Jim Wickman and I’m in the office of campus ministry here at Georgetown University. Let’s all sing together “Amazing Grace” found in your program. Please stand.

Rachel Swarns 00:23

What I learned was that the Jesuit priests who founded and ran Georgetown happened to be some of the largest slave owners in Maryland. I don’t think most of us have given much thought to how slavery fueled the growth of institutions, not only in the south, but in the north. And how many of those institutions are you know around us today.

Kirsten Mullen 00:53

The harms were not limited to the human chattel that they casually bought, bartered, and leverage So, in the case of a Georgetown University, it’s quite likely that parishioners, you know, under the Jesuit’s care, modeled their behavior after that of these officials and justified their ownership of Black bodies.

Rachel Swarns 01:17

You know, I was kind of like, “Catholic priests owned slaves?” I was like, “What, universities benefited from slavery?” You know, at the same time, I was thinking to myself, but of course they did. Of course they did.

Osha Davidson 01:50

Priests owned slaves? Universities owned slaves? As “New York Times” contributing writer Rachel Swarns said in the opening: Of course they did. Georgetown University was founded by Jesuit missionaries in 1789, the same year that America’s constitution was signed. Like the nation itself, the school was built upon the rock of chattel slavery.

I’m Osha Gray Davidson, producer and host of The American Project. In this episode, number nine, we’ll look at how the nation’s oldest Catholic institution of higher education was founded on the backs of enslaved Black people. We’ll also hear how Georgetown and other schools are grappling with that history. And we’ll speak with Kirsten Mullen, who you also heard in the opening. Mullen is co-author of the best-selling book, “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century.” She’ll help us put Georgetown’s struggle in perspective within the larger national movement for reparations.

Osha Davidson 02:59

You’re a contributing writer at the “New York Times” and an associate professor at NYU, is that right?

Rachel Swarns 03:05

Yeah, yeah. So I spent, you know, 23 years at the Times and joined…

Osha Davidson 03:10

Rachel Swarns

That’s Rachel Swarns, whose 2016 story about Georgetown’s past revealed just how deep slavery runs in even America’s most elite institutions. Her article, which has been downloaded more than a million times, created a stir far beyond higher ed. But Swarns became interested in Georgetown because it overlapped with an entirely different subject.

Oprah Winfrey 03:34

Welcome, Michelle Obama!

Osha Davidson 03:37

The future First Lady didn’t attend Georgetown. In her senior year at a Chicago public high school she talked with an advisor about the college she aspired to: Princeton University,

Michelle Obama 03:49

But here I walked into this room with a woman who really didn’t know me because it was a big high school, and she had to make a quick assessment. And her assessment could have been, and I don’t know, was: Grade point average? Yeah, you’re a good student. You know, your scores are good. You’re Black. You’re here in this public school. Maybe you’re stretching. She didn’t try to figure me out. She just decided that the dream I presented was wrong.

Osha Davidson 04:16

Ignoring the counselors assessment, Michelle Obama applied to Princeton, was accepted, and excelled there as a student. Like Georgetown, Princeton was also deeply rooted in slavery. Founded in colonial New Jersey in 1746, Princeton’s first trustees were prominent citizens, men like Aaron Burr, Sr., whose son Aaron Burr, Jr., would be the third Vice President of the United States. There were seven original trustees. All of them were slaveholders. After she graduated with honors from Princeton, Michelle Obama set her sights on the nation’s most prestigious law school.

[Singing “Fair Harvard”]

Osha Davidson 05:11

Harvard University was founded more than a century before Princeton. In fact, Harvard was the very first institution of higher learning in colonial America. The school was created by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the first American colony to legalize slavery. Harvard’s connection with slavery continued uninterrupted for 230 years until the Civil War.

Osha Davidson 05:41

In 2009, Rachel Swarns wrote an in-depth article about Michelle Obama’s roots, a piece that led to a prize-winning book on the subject, “American Tapestry.”

Rachel Swarns 05:52

One of the big focuses was about her great-great-great grandmother who was an enslaved woman who was valued at about $450 in the 1850s, and her great-great-great grandfather whose identity was a mystery. And doing this research was completely new. And it showed me something that I didn’t really understand until then, just how slavery shaped so many of our contemporary families that so many of us Black, White, and in between, right? And then I heard about this slave sale in 1838. For me personally, it was a chance to look beyond, to take this work that I had begun to do on how slavery impacted families to look at how slavery impacted institutions.

Rachel Swarns 06:56

The Jesuit priests who founded and ran Georgetown happened to be some of the largest slave owners in Maryland at the time. And when the college fell on hard times, they did what people of that era did. They tried to raise money and they sold off their assets, a lot of their assets. And those assets happened to be human beings: 272 men, women, and children who were sold to save the school. And they were successful. You know, Georgetown survived and became one of our elite universities, but it was obviously at a terrible cost.

Rachel Swarns 07:43

It’s not that there weren’t dissenting voices, there were. But for the most part, this was not controversial. And in fact, because Catholics at the time in Maryland in the colonies were discriminated against and marginalized. too, it was a way of becoming an accepted part of a community which valued slave-holding as a sign of prestige and wealth.

“While the white skin made the Irish eligible for membership in the White race, it did not guarantee their admission. They had to earn it.” Noel Ignatiev, “How the Irish Became White.”

Osha Davidson 08:10

It’s important to remember that in America’s early years, the elites were Protestant and mostly English. They despised Catholics who are mostly Irish. In his book, “How the Irish Became White,” Noel Ignatiev wrote, “While the white skin made the Irish eligible for membership in the White race, it did not guarantee their admission. They had to earn it.”

The Georgetown sale was worth 3.3 million in today’s dollars. In essence, Georgetown bought its whiteness at the cost of 272 Black lives. Most institutions of the era benefited from slavery directly through owning slaves or indirectly being funded through the trade in Black lives. But according to Swarns Georgetown’s situation was unusual.

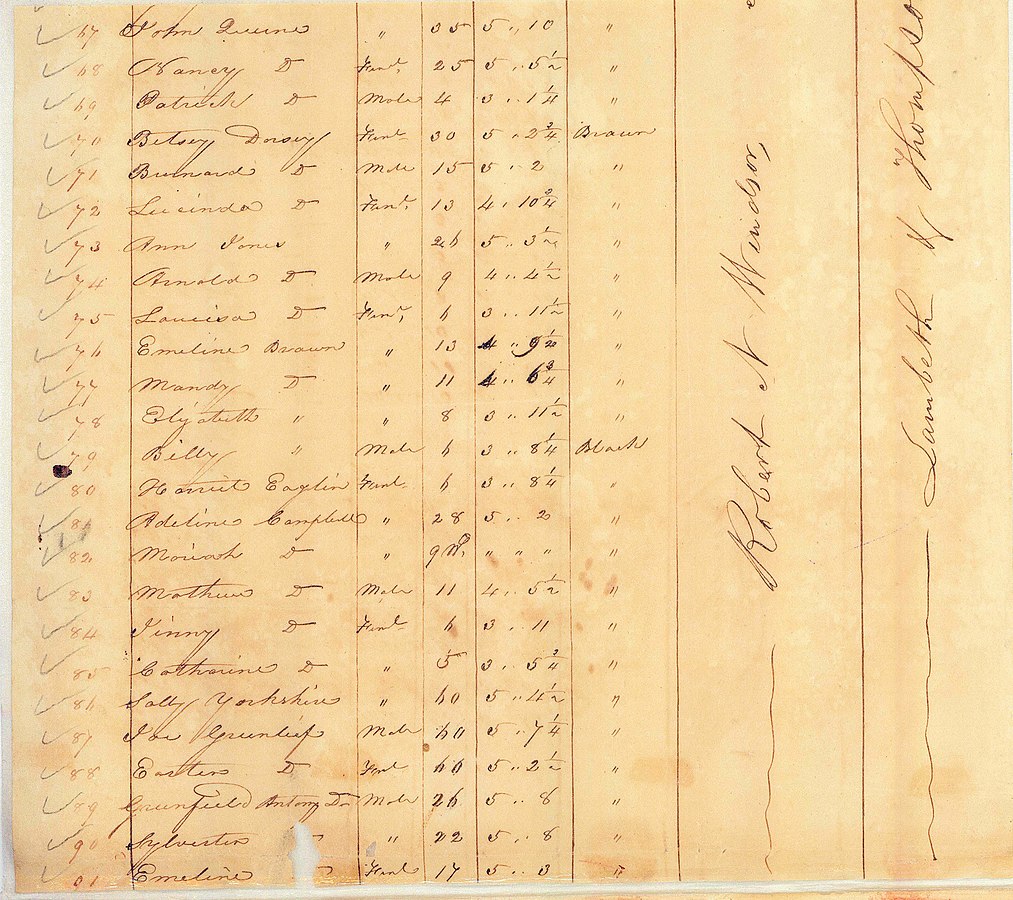

Manifest of the ship Katherine Jackson, carrying enslaved people from Georgetown to Louisiana in 1838.

Rachel Swarns 08:58

So Georgetown stands out for a number of reasons. One, the slave sale itself of 1838 was one of the largest documented slave sales. And the Jesuits who had owned and sold slaves for decades, were great record keepers. I mean, they documented a ton. And so unlike other institutions, other colleges and universities which are also you know, digging into their histories and trying to find out what can be found, in the instance of Georgetown, their names, their names, their ages. You know, you can see the shape of the people in the records and that is extraordinarily unusual.

Osha Davidson 09:43

For many devout Americans today, Black and White, the notion of spiritual leaders pursuing good works while at the same time buying and selling human beings, causes a kind of religious vertigo.

Rachel Swarns 09:56

I think it’s pretty astonishing to a lot of people First of all that, you know, Catholic priests owned slaves to start with. And secondly, that, really this institution have relied on enslaved people, their labor and the profits from the sales of their bodies, to run the school. That was a key funding stream for the university and for the priests themselves. I mean, slavery helped finance the livelihoods and the mission projects of the Catholic Church at that time.

Osha Davidson 10:34

For Swarns, the story was deeply personal for more than one reason.

Rachel Swarns 10:40

In addition to being an African American, I’m Catholic. I go to Mass on Sunday. Many of my family members were educated by priests and nuns and I had no idea. And I think even among some Black Catholics this is uncomfortable history. But it’s something that we all have to reckon with.

Osha Davidson 11:03

We’ll look at how Georgetown and other schools are attempting to reckon with this uncomfortable history after this short break.

Osha Davidson 11:13

You’re listening to The American Project. You can find more on today’s subject and about the podcast in general on our website, www.TheAmericanProject.us. Just click on Episode Nine and you’ll find a program transcript, photos, and additional resources. And please remember to subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Osha Davidson 11:41

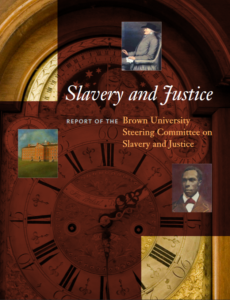

So how exactly does an elite University reckon with a discovery that they owe their very existence to slavery? Well, fittingly for an institution of higher ed., Georgetown University began the process by appointing a working group to study the question and come up with a list of recommendations. Commissioned in 2015, the Georgetown Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation issued its final 100 page report a year later. Before we get to those specifics, it’s important to know that Georgetown didn’t have to start from scratch. A decade earlier Brown University had had its own moment of reckoning. Here’s Ruth Simmons, Brown’s president at the time, explaining what happened at her institution.

Ruth Simmons, President of Brown University, 2001-2012.

Ruth Simmons 12:28

Well, the Brown story came about because a number of people decided that certain institutions should be sued and required to disgorge profits from slavery, and they had identified several universities as likely targets. And Brown was one of these institutions.

Osha Davidson 12:52

Simmons went to her PR person and instructed her to search the records for any links between Brown and slavery and report back what she found.

Ruth Simmons 13:01

And so her answer was there is no connection between Brown and slavery.

Osha Davidson 13:06

But Simmons wasn’t satisfied. In April 2003 she created the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice to begin its work by conducting a full historical investigation.

“Everybody linked our study to my race. And that is to say, here is Brown University, dealing with reparations and guess what? The President is African American….You know, becoming the first African American president of an Ivy League University, my mind was all about, okay, I need to do this well, so that I won’t be the last African American president of an Ivy League University.” Brown President Ruth Simmons.

Ruth Simmons 13:18

So that’s how it started. Just trying to get to the truth and I thought every alum of Brown needed to know the truth about our history. And it turned out to be pretty amazing because that history was replete with involvement in slavery because virtually every shopkeeper, every merchant, everybody who had any money in Rhode Island at the time of the founding of Brown, was involved in some way in slavery.

Osha Davidson 13:47

In the late 1700s, raising money for the school, then known as Rhode Island College, President James Manning turned to a prominent local family which was involved in the slave trade: the Browns. In honor of their support the school was renamed for them.

Ruth Simmons 14:04

And they raised money from many people in Rhode Island, and then formed a group, a board, the corporation. And almost all of them were involved in slave trading. So probably most of the funds that we got in those days came from some association with slavery.

Osha Davidson 14:23

When Simmons commissioned the steering committee in 2003, some objected to even that modest step. For Simmons in particular, there were landmines everywhere beyond those that Georgetown’s president Jack DeGioia would find more than a decade later.

Ruth Simmons 14:38

First of all, the press were very, very hard on us, I think at the time we undertook our study, because everybody linked our study to my race. And that is to say, here is Brown University, dealing with reparations and guess what? The President is African American. So, you know, first of all, we have to deal with the fact that Jack can do this and there’s one perception. I can do it and there is a very different perception all because of the matter of race. You know, becoming the first African American president of an Ivy League University, my mind was all about, okay, I need to do this well, so that I won’t be the last African American president of an Ivy League University.

Osha Davidson 15:31

At the same time, Simmons was also acutely aware that her decisions would be judged by Black Americans.

Ruth Simmons 15:39

I also want to be able to go back to my community and have them respect me. So what I can’t do is be just like, Shirley Tilghman at Princeton, just like Larry Summers, you know, at Harvard, I can’t, I cannot do that because people will recognize a failure in me, or they should, if I am just another Ivy League president. So in the back of my mind, I knew that I had to be my own kind of President – not just a good president for Brown, but a good president in the context of where I came from.

Osha Davidson 16:26

She told the committee to consider a wide range of issues relating to Brown’s connection with slavery. But Simmons had placed one topic off limits: reparations. As she put it earlier, the perception was:

Ruth Simmons 16:40

Here is Brown University, dealing with reparations and guess what? The President is African American.

Osha Davidson 16:49

In 2003 Simmons believed that racism would have scuttled any attempt by her administration to even discuss reparations.

Brenda Allen 16:59

So, President Simmons got death threats. Real, true death threats.

Osha Davidson 17:03

That’s Brenda Allen, a member of the steering committee and associate provost at Brown. As liaison to the president’s office, Allen had a unique view of the battles inside and out over what Brown was attempting to do. Her remarks are from a 2017 presentation at Duke University and we’ll give a link to that talk in the transcript.

Brenda Allen 17:23

People threatened to abandon their support. So there were people who were donors who just felt like if you had this discussion, you’ll never get another one of my dimes, right? But you’ve got to say, this is bigger than you.

Osha Davidson 17:41

The Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice took three years to research and write their report.

Brenda Allen 17:48

“Slavery and Justice,” Brown University Report.

We submitted it to the President once. She didn’t like the recommendations. She said they weren’t bold enough so she gave it back. And so we had to sit again and write it some more. Finally submitted the report. It was released in the fall of 2006.

Osha Davidson 18:05

The committee made 33 recommendations covering a wide range of areas.

Brenda Allen 18:09

An urban education program that comes with full fellowships, a center for postdocs and visiting scholars, a fund for the children of Providence because it has some of the worst school systems in Rhode Island…

Osha Davidson 18:19

One theme united them: a principle that came straight from Ruth Simmons.

Brenda Allen 18:23

She wanted to be about the things that the university could do the best and that was to use these intellectual resources to really raise a rigorous conversation. Her goal was to hopefully help the campus in particular, but maybe the nation and the world come to a deeper understanding about the complexity that’s wrapped around this whole conversation that we so easily put in this label of reparations.

Brenda Allen 19:00

And I think if we couch our mission for any of these activities in the context of what universities do, then you always have the answer when people are saying, what are you doing this for? Well, that’s what we do. At universities we look at questions, we look at controversial things, we try to understand how the past and the present come together.

Osha Davidson 19:25

The editorial board of the “New York Times” praised what they called the Brown Report for this aspect. They wrote, “The value of this exercise was to illuminate a history that had been,” and here the Times quoted the report, “largely erased from the collective memory of our university and state.” One recommendation that brown implemented along these lines was the commissioning of a sculpture.

Osha Davidson 19:52

On a windy winter day earlier this year, Maiyah Gamble-Rivers led students on a Slavery and Legacy Walking Tour of the Brown campus.

Maiyah Gamble-Rivers 20:02

So, we can make our way to the memorial itself…

Osha Davidson 20:06

One of the students reads the text that accompanies the memorial sculpture.

Dedication of Brown University’s Slave Trade Memorial sculpture.

Student 20:11

This memorial recognizes Brown University’s connection to the transatlantic slave trade and the work of Africans and African Americans enslaved and free who helped build our university, Rhode Island, and the nation.

Osha Davidson 20:24

Gamble-River’s created the tour as part of her job as program director of what could be the most important and lasting result of Brown’s effort at redress: the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice.

Video 20:38

The center is an institution that confronts one of the central questions of American and world history. And that is slavery.

Osha Davidson 20:48

In case you couldn’t tell from the upbeat music, that’s a short clip from Brown’s own lushly produced promo. But the center’s work itself is about substance, not style. The center sponsors faculty, graduate, and postdoc fellows doing research on issues of slavery and justice. It collaborates with universities and museums around the world and hosts a program for local high school students, which includes a weekly class at the center, and a week-long tour of historically important movement sites throughout the South. The center has hosted hundreds of public programs, including art exhibitions, and more than 100 panel discussions and public lectures, all available as videos on the center’s YouTube site. A decade after the Brown report was released, former president Ruth Simmons had this to say about the experience.

Ruth Simmons 21:42

The most important thing is for us to learn about this is that silence is poisonous.

Osha Davidson 21:49

It was a lesson that Georgetown University was then just beginning to learn.

Father David Collins 22:09

So good evening, everybody. And thanks for joining us at this Facebook Live conversation that we’re having here in the Alumni House at Georgetown University. As most of you surely know, today the university released the report of the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation. My name is Father David Collins. I’m a professor in the history department. I have been the chair of the working group. It has been as I’m also sure you know…

Osha Davidson 22:39

Also speaking at the 2016 event was Georgetown Professor Marcia Chatelain, a member of the working group who earned a master’s and doctoral degree at Brown University while that institution was reckoning with its past.

Marcia Chatelain 22:53

I think for me, what I point to in the report is that the anxiety and fear that when you change the names of buildings or when you change a process at a university, it doesn’t collapse. I think that some of the most disingenuous discourse out there about change is: Well, you’ll ruin the whole enterprise. We know that that’s not true. And at the same time, though, that these changes, if they happen outside of a context in which real structural issues aren’t addressed, then they are just that: empty gestures.

Osha Davidson 23:26

What Georgetown needed to do in 2016, was what much of America is struggling with today in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd: Trying to find the right response to systemic racism that has been the norm in America for centuries. Georgetown renamed prominent buildings on campus, just as some local governments today are removing statues and renaming sites that honor Confederate defenders of White supremacy.

News clips 23:55

Across the country, Confederate monuments have been coming down…has ordered the removal of Confederate monuments and markers around Jacksonville… another southern monument falls in the former capital of the Confederacy…Turning now to a developing story in Henry County, that’s where a Confederate monument is no longer standing. Crews are…Governor of Mississippi has officially removed the Confederate battle emblem from the state flag, the last one in the nation with that design.

A statute of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson comes down in Richmond, VA.

..Earlier this month, NASCAR banned Confederate flags from its racetrack…This effort would rename 10 military bases. Fort Benning in Georgia, Fort Hood in Texas and Fort Bragg North Carolina…celebrated Thursday at the graffiti-covered and long controversial statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee….Well, another historic day in Richmond as the statue of Jeb Stuart is brought down from its pedestal…protestors bringing down the statue of Jefferson Davis… John C. Calhoun…the spirit of the Confederacy…statue of Hey Reb!…the Confederate memorial in front of the Gadsden county courthouse…Huntsville, Alabama…downtown Indianapolis…Montgomery, Alabama… Phoenix, Arizona…Nashville.

Osha Davidson 25:02

Okay, symbols are important. But dealing only with symbols while leaving structural racism intact mocks the very notion of justice. Brown’s emphasis in 2003 was on truth telling. Would Georgetown in 2016 go beyond that? Georgetown working group member and Professor of History and African American Studies, Maurice Jackson, put it this way:

Maurice Jackson 25:26

I’m a descendant of slaves. If it is true that the truth sets you free? Well, it’s partly true because we’ve known the truth of many years and we’ve not completely been set free. But it’s the road to freedom.

Osha Davidson 25:39

As “New York Times” reporter Rachel Swarns said earlier, at least two things made Georgetown’s 1838 slave sale unique. First, it was one of the largest sales of enslaved people in US history. Second, unlike most slaveholders, the Jesuits kept precise records of the 272 people they sold. The GU272, as they’re now called, included entire families. In November 1838, the GU272 were loaded onto ships. The manifest of a three-master named the “Katherine Jackson” has been found, so it’s known that it carried 120 enslaved people. The oldest was 70. The youngest, just two months. The human cargo arrived in New Orleans on December 6th. They were split up and taken to sugarcane plantations in southern Louisiana.

Adam Rothman 26:31

The unfortunate thing about the historical work that had been done is we…nobody really asked what happened to those people? What happened to the community that was sold in 1838? The question was just never asked.

Osha Davidson 26:45

That’s Adam Rothman, a history professor at Georgetown and a member of the working group. Rothman spoke at a public forum in New Orleans in 2016. Two other participants in that forum knew what happened to at least some members of that community

Sandra Green Thomas 27:00

My name is Sandra Green Thomas. For the purposes of this evening, I think the most important thing you need to know about me is I’m a descendant. I’m a descendant of William Harris and Betsy Harris from…

Cheryllyn Branche 27:11

Good evening, everyone. My name is Cheryllyn Branche. I’m also a descendant. My ancestors were Hillary, and Hinny Ford and their infant son, Basil Ford, along with four siblings, who was sold in 1838, from Georgetown, and sold to a plantation called Chatham.

Osha Davidson 27:34

Cheryllyn Branche learned about her link to the GU272 a few months before the panel discussion when she answered her phone, and a stranger said:

Richard Chellini 27:44

This is Richard Chellini. I’m an alumnus of Georgetown.

Osha Davidson 27:48

Chellini told Branche about her ancestors who had been sold by Georgetown – information she had never heard before. The owner of a software company, Chellini was an alum but otherwise had no links to Georgetown.

Richard Chellini 28:01

I’m a moderate Republican, an Italian American, have no connection to African Americans or the history of slavery.

Osha Davidson 28:10

What Chellini did have was a strong sense of right and wrong. He was shocked when he learned of the slave sale and the fact that no one from his alma mater had tried to find out what happened to those who had been sold. So he did it himself. Chellini hired a genealogist and got to work. Today, his organization, the Georgetown Memory Project has tracked information on 230 of the GU272 and located 9,982 descendants. Recently, I talked with one of them, a young man named Shepard Thomas from New Orleans, a recent graduate of Georgetown University.

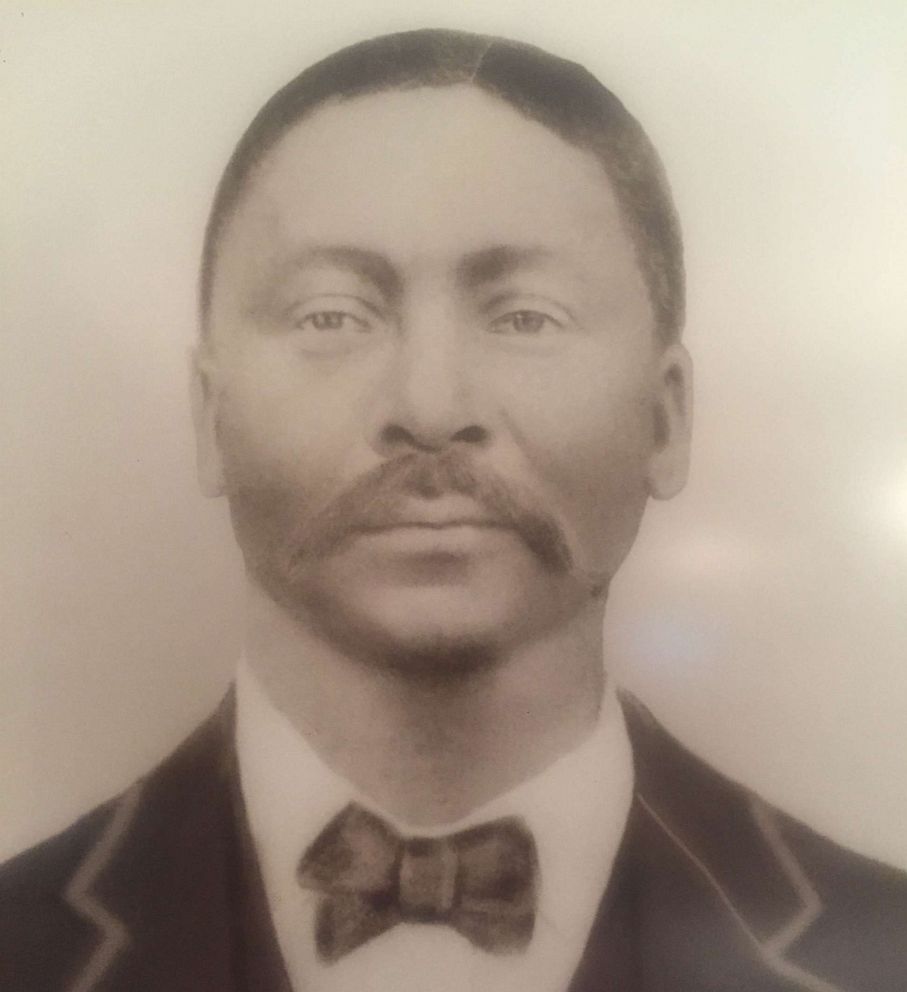

William Harris, 1901, son of Sam and Betsy Harris, enslaved by Georgetown and sold to a Louisiana plantation in 1838.

Shepard Thomas 28:53

I came to Georgetown when I was a sophomore in college. I transferred here and I’m also descendant of the 272, the original people sold by Georgetown in 1838.

Shepard and Elizabeth Thomas at the grave of their great-great grandfather, William Harris.

Osha Davidson 29:02

When did you find out? Did you always know that?

Shepard Thomas 29:05

So, I actually I didn’t know until like my senior year of high school. So it was actually like, two weeks before I was graduating, I figured out about it.

Osha Davidson 29:14

What did it mean to you personally to learn that family history?

Shepard Thomas 29:17

It meant a lot to me because like, speaking to a lot of students at Georgetown University who are like African American, a lot of them don’t know, like, they can’t trace their lineage back and find out where they’re from. So me being able to do that, it meant a lot, knowing that they were on this campus, and they were sold down. It hurt me. It hurt me personally. So when I was able to connect the dots and my family’s history, I was like, wow, I have to come here and I have to be a part of something that honors their legacy.

Osha Davidson 29:42

One recommendation made by the Georgetown working group was to provide financial aid to the descendants of the GU272 to attend the University. So I asked Thomas:

Osha Davidson 29:53

Did they do anything to increase financial assistance?

Shepard Thomas 29:55

No.

Osha Davidson 29:56

None?

Shepard Thomas 29:57

No. If you find out let me know.

Osha Davidson 30:02

Instead of scholarships, Georgetown opted to grant legacy status to those descendants of the GU272 who apply to the university. Their applications, like those of the children of alumni and faculty, get a more thorough review. Georgetown’s Adam Rothman.

Adam Rothman 30:20

It’s not a huge thing at all. But it is a recognition that they’re part of the community and deserve the same amount of consideration.

Osha Davidson 30:32

Here’s what Shepard Thomas had to say about legacy status.

Shepard Thomas 30:36

There are more descendants who have been denied by Georgetown than have been accepted. So, like this isn’t like a guarantee you’re getting into Georgetown type of thing. What did the university really promise descendants? I don’t really see anything.

Osha Davidson 30:47

Like renaming a building, the benefit of granting legacy status is primarily symbolic. From the beginning the call for change at Georgetown, both symbolic and substantive, has come from a group we haven’t mentioned yet: the student body. Here’s “New York Times” writer Rachel Swarns.

Rachel Swarns 31:05

Students have been really important actors in all of this. You know, Georgetown had started and had set up a committee to examine its history when it opened some buildings that carry the names of the college presidents and priests who had been involved with this slave sale. And students protested and the names were changed. But that protest was what, you know, sparked the interest of this Georgetown alum who said, “Okay, we’re changing the names of the schools. But what happened to these enslaved people when they were sold? What were their descendants?”

So it really sparked that process of identifying these folks. And then, you know, in 2019, it was students again who said, okay, Georgetown had set on this path, a path that really made it stand out among universities in the country, but a path that students felt was too slow, taking too long in terms of addressing the needs of descendants. And so it was students who said, okay, we’re going to have a referendum and we are voting to in effect tax ourselves by instituting a student fee that will create a pool of money that we would like to go to descendants, explicitly to help descendants as a form of reparations. It’s also interesting to note that this vote to create this fund to benefit the descendants of enslaved people sold, owned and sold by the institution, this vote was passed at a majority White institution. An overwhelmingly White group of students. So it’s…to me that’s interesting, too. And it says something about where I think the country’s come on this issue that, you know, a predominantly White student body would take that step.

Osha Davidson 32:54

Although the Georgetown student body voted to approve the fee, the administration rejected the idea. President DeGioia said that the school would “embrace the spirit of the student proposal,” and commit to raising $400,000 annually to fund projects like school assistance and health care clinics in descendant communities in Louisiana. That program is set to launch in the next month or two. But descendants of the GU272 already objected to the administration’s plan in a video op-ed published by the “New York Times” this past February. Here’s descendant, Jean Dorsey.

Jean Dorsey 33:32

I don’t think they should go bankrupt. But $400,000 is not going to do it.

Maxine Crump 33:36

I think Georgetown has such an opportunity here to take the lead on this.

Osha Davidson 33:40

And that’s Maxine Crump.

Maxine Crump 33:42

We don’t need to make White people wrong. We don’t need to make Georgetown wrong. We need to ask ourselves, what do we need to do to ensure that all of Americans have full access to every right that it means to be in America?

Osha Davidson 33:57

The problem may be that Georgetown, or any university, can’t on its own achieve anything near Crump’s goal. Kirsten Mullen is the co-author of the book, “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century.” Mullen has a simple but pointed question about Georgetown’s effort.

Kirsten Mullen 34:22

What exactly would the university be achieving? I mean, there are other institutions that have done similar things. Princeton Theological Seminary will set aside $27.6 million from its endowment to fund a set of initiatives that I think will include scholarships, curricular reforms, and community outreach.

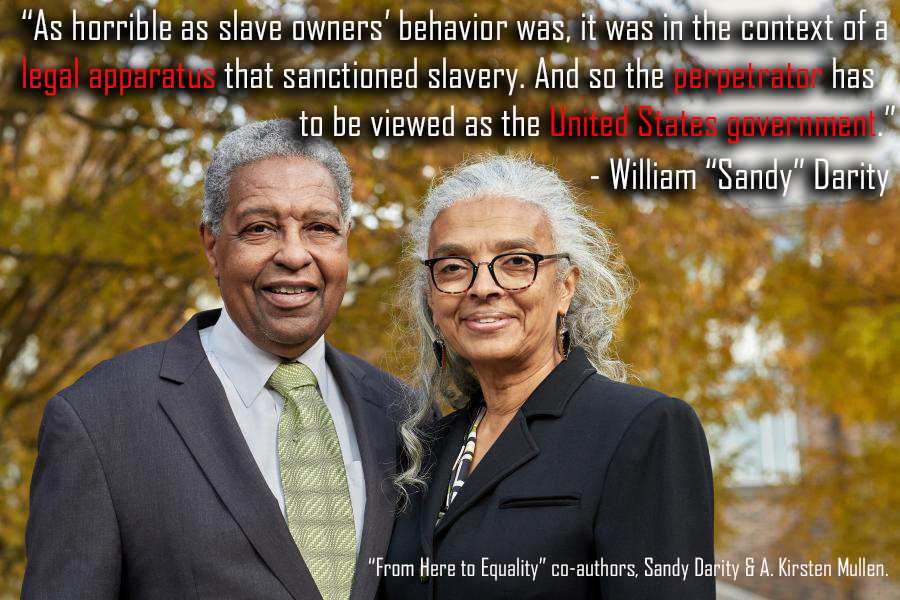

“From Here to Equality,” co-authors, Sandy Darity and A. Kirsten Mullen.

Osha Davidson 34:41

It’s not that there’s necessarily anything wrong, per se, about the programs at Brown or Georgetown or any other institution of higher ed. The problems is that by definition, these are piecemeal efforts, necessary, perhaps, but insufficient.

Kirsten Mullen 34:57

The whole part about the piecemeal effort is ultimately it’s a distraction if it takes our focus away from the wealth gap, which I think scares people to death. But that’s really the key.

Osha Davidson 35:11

That racial wealth gap? It scares people because of its enormity. Sandy Darity, Samuel Dubois Cooke, Professor of Public Policy at Duke University, and co-author of “From Here to Equality” explains.

Sandy Darity 35:24

If you were to look at the full gap that would be represented by the difference in the mean values of wealth between Blacks and Whites, then we’re talking about a differential per household in the vicinity of $800,000. So these are immense differences. Another way to think about it is Black Americans constitute about 13% of the United States population but hold or own less than 3% of the nation’s wealth.

Osha Davidson 35:55

Darity estimates that it would cost between $10 and $12 trillion – yes, trillion with a “t” – to close the racial wealth gap. Again, Kirsten Mullen.

Kirsten Mullen 36:06

The goal of a reparations program should be the elimination of this huge gulf in Black-White wealth. And none of these programs, I mean, Georgetown is just one of many that has put forth, you know, some type of “reparations” program, and none of them would really move the needle. We applaud these measures, and we hope that these institutions will actively support a comprehensive program of national reparations.

Osha Davidson 36:39

So to recap just a bit: In 2003, Brown University set a new standard by uncovering their ties to America’s original sin of slavery and making that history public in a big way. In 2016, Georgetown went even further, moving from truth-telling to broader engagement and constructive action. If Darity and Mullen are right, perhaps the next step in this journey to racial equality is for institutions to go beyond individual reckonings. Maybe their task in 2020 is to speak with a single voice in support of a national program that will help to make us truly one nation with liberty and justice for all Americans.

Osha Davidson 37:31

You’ve been listening to “The American Project” – independent reporting on a democracy in the works. I’m your host, Osha Gray Davidson. Season One is a deep dive into the issue of reparations for slavery and its legacy.

Thanks to Rachel Swarns for talking at length about her work reporting for the “New York Times” on Georgetown’s reckoning with its past. Swarns is currently working on a book for Random House on that subject. Thanks also to Shepard Thomas, the GU272 descendant who recently graduated from Georgetown, and to Maiyah Gamble-Rivers from Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, for allowing us to use her recording of the school’s Slavery and Legacy campus tour. To the peerless George Webber: thanks for bringing voices from the distant past into our presence.

And last but certainly not least, thank you once again to the dynamic duo of A. Kirsten Mullen and William A. Darity, co-authors of “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century,” published in April by the University of North Carolina Press and already in its third printing. If you have a question or comment about anything on our podcast, or something we should have included but didn’t, we want to hear from you. Go to our website, www.TheAmericanProject.us. And please subscribe to our podcast in iTunes, GooglePlay, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening.